iwwage_admin

Social protection through a digital tool reaches the milestone of 100,000 applications

“Living in a tier-2 city in the state of Rajasthan in India, I had to take half a day off from work to apply for an Aadhaar card. I had to travel to the Aadhaar center, which was about 7kms away, stand in line for one hour for my turn to come, only to realize that the machine was not accepting my iris scan. The three officials at the center could not figure out the problem, after struggling for 20 minutes. I was told to wait for another half hour, for the machine to start working. After half an hour, the machine started working and my application was submitted. The entire process took 4 hours. The majority of people living in rural areas do not have the luxury to step away from their work and lose out on daily wages.

The time spent on this process can be minimized for government entitlements that require in-person presence of the applicant and eliminated for entitlements that do not require the in-person presence of the applicant” – Anoushaka

Poor households often rely on government entitlements for mitigating risk and livelihood development. With the aim of increasing information about and uptake of government entitlements, and with the support of the State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM) in the state of Chhattisgarh, IWWAGE – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University, and Haqdarshak Empowerment Solutions Private Limited (HESPL), is implementing a project for promoting government entitlements through women self-help group (SHG) members as agents. As part of this project, self-help group (SHG) members receive training on how to use a digital application, Haqdarshak, which provides a ready reference of more than 200 central and state government welfare programs, their benefits, eligibility criteria, documents required, and the application process for each scheme. The trained agents offer door-to-door services to their respective communities using the app to support households to gather information and apply for government programs, for a small fee.

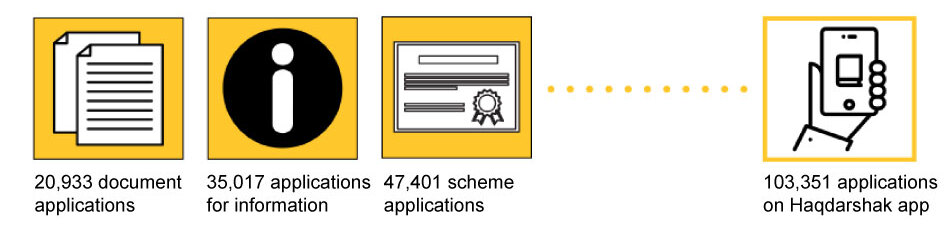

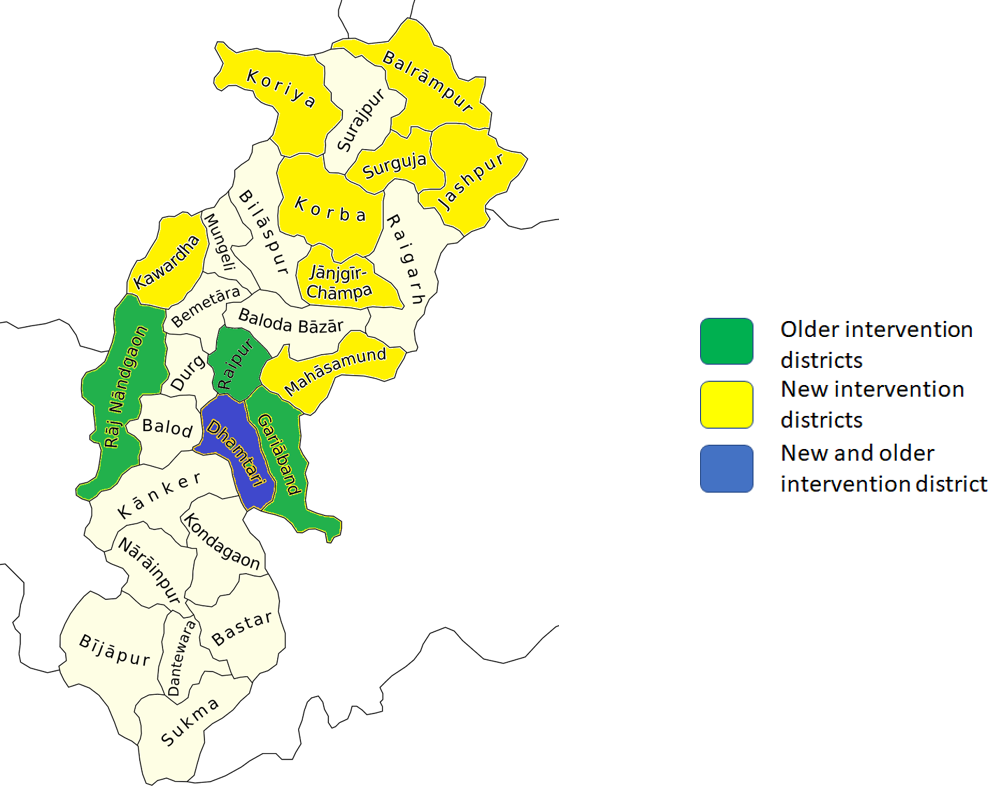

The project is being implemented in four districts of Chhattisgarh (Raipur, Rajnandgaon, Dhamtari and Gariyaband) and over the past year around 2,700 SHG women have been trained to become Haqdarshak agents. Among all of the trained women around 1,000 performed their duty actively and have received over 100,000 applications for a wide range of government entitlements[i].

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

- 34% of the total applications are for COVID-19 related informational schemes. These include availability of free ration at PDS shops, cash transfers to women PMJDY account holders, distribution of free food packets for children enrolled in government anganwadis, and availability of free gas cylinders under the Ujjwala Yojana. Providing information to the rural poor about the availability and the mode of access for these additional benefits is an important step in ensuring that the benefits reach the intended beneficiaries. In such situations, the Haqdarshika’s role was to inform citizens enrolled in these schemes of the additional benefits available they can avail and, when necessary, support them to access these benefits.

- PAN cards are the most sought-after document, accounting for 80% of the total applications for documents. Insights from our fieldwork suggest that people in rural areas perceive the PAN card as a document required for opening of bank accounts and it is also promoted as such by many application touch-points.

- Among welfare schemes, insurance programs like the Pradhan Mantri Bima Suraksha Yojana (PMSBY), Ayushman Bharat and Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) are the most popular schemes among applicants.

Among the four districts in which the program was implemented, Raipur district accounted for around 48% of the 100,000 applications, followed by 38% from Rajnandgaon, and the remaining 14% of the applications were from the Dhamtari and Gariyaband districts. However, an important caveat is that the program targeted Raipur district first, which means that the intervention has been running in the district for a much longer time. The intervention has also targeted fewer blocks in Dhamtari and Gariyaband, as compared to Rajnandgaon and Raipur districts.

Reaching the 100,000 applications mark on the Haqdarshak platform has been an important milestone for the project. However, there have been several challenges in implementation along the way and the program team is working towards developing solutions to address these.

Dropout of Haqdarshikas from the program

Of the 2,700 women trained to be Haqdarshikas, only 603 are active as of September 2020. A Haqdarshika is considered ‘active’ if she has processed at least one application in a given month. Some of the factors which may account for this trend are:

- Some of the training participants might not pass a post-assessment test, which is required to conduct transactions on the platform.

- 60 to 80 percent of the agents drop out after the fourth month of activity. This could be due to saturation of applications for schemes and documents for which Haqdarshikas (HDs) have most information. Refresher trainings are being conducted with HDs who dropped out of the program, to overcome this challenge.

- Other reasons include damages to their smartphone, shared usage of smartphone resulting in non-availability of the phone for the Haqdarshikas, restrictions on mobility from their families, lack of entrepreneurial spirit etc. This is clearly an issue of targeting. Selecting suitable candidates for the training requires time and effort, since potential participants need to be screened against certain minimum requirements and informed about the expected commitment, type of work, and remuneration of the program. Ensuring greater buy-in and providing a higher degree of support to local government officials is essential to make any progress on this issue.

Long processing time for applications

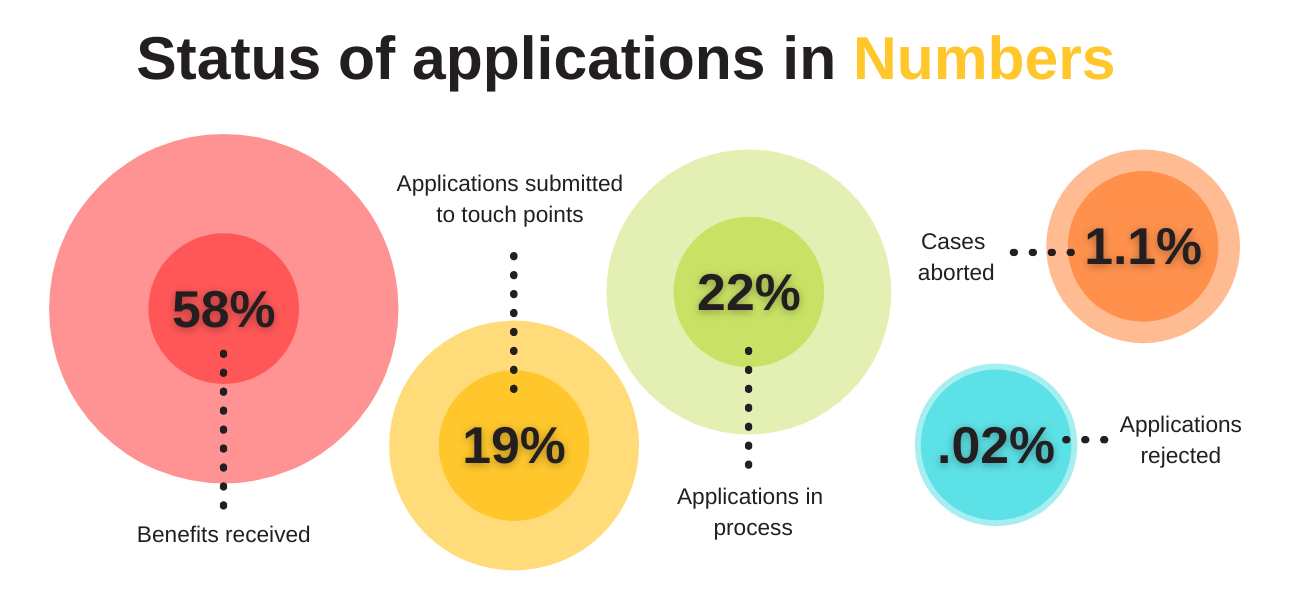

While the 100,000 applications milestone suggests that there is a high demand for government entitlements among rural households, not all the applications have translated to benefits received by the citizens. This could potentially be explained by the long processing time and procedural delays for certain schemes and documents. The project team is exploring ways to delve deeper into the reasons for delay and also ways to tackle this challenge.

Technology needs a sustained value proposition

Another reason why we see less than 100% conversion of applications submitted to benefits received is that Haqdarshikas at times do not update the status of the application itself. This indicates that while the citizen may have received the benefit, the status displayed on the app shows that the application is ‘pending’. This could be due to the fact that Haqdarshikas do not follow up on the processed applications in a timely manner or to the citizens not feeling comfortable providing proof of receipt of the document or scheme they applied for due to privacy concerns. Both instances point to a lack of practical and/or material incentives to update the status of the applications, besides the Haqdarshikas’ own diligence. This issue could be addressed, for example, by a change in the remuneration structure of the model or by increased integration of the app in the government’s own application system, thus reducing the need for manual inputs.

In the coming months, the Haqdarshak program will be scaled up to 21 different blocks in nine additional districts of Chhattisgarh. In these blocks, with the support of CGSRLM, the implementation will focus on Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) and Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) to improve their access to information and in turn, government entitlements.

[i] [i] These applications were received between June 2019 and September 2020.

Anoushaka Chandrashekar is a Project Manager with LEAD at Krea University and Raka De is a Research Associate with LEAD at Krea University.

Digital Solutions for SHGs in Chhattisgarh

Government entitlements are often the primary source of social protection for poor households. With the aim of increasing information about and uptake of government entitlements, and with the support of the State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM) in the state of Chhattisgarh, IWWAGE – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University and Haqdarshak Empowerment Solutions Private Limited (HESPL),is implementing a project on promoting government entitlements through women self-help group (SHG) members as agents. Within this project, self-help group (SHG) members are trained on a digital application called Haqdarshak. The digital tool, Haqdarshak, is an innovative mobile application developed by HESPL. The application provides a ready reference of more than 200 central and state government welfare schemes and programmes, their benefits, eligibility criteria, documents required, and the application process for each scheme. These SHG women members, known as Haqdarshikas, in turn go door to door to households within their communities to provide information and enable households to apply for these government programmes, for a small fee.

The research team at IWWAGE – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University, conducted a survey of 411 Haqdarshikas in September and October 2020 to understand factors that influence retention and drop-out from the programme. This cohort of Haqdarshikas received training between August 2019 to February 2020. The survey also delved into the impact of COVID-19 on the work of the Haqdarshikas.

IWWAGE-ISI Briefs: Analysing the constraints to women’s economic participation in the context of pandemic

As a part of the project undertaken by Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) and IWWAGE, a set of four briefs have been developed to understand the challenges faced by women while engaging in remunerative economic activities. The briefs also evaluate the existing programmes with gender lens, that aim at unleashing women’s economic potential fully in India, and offers policy recommendations. As the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have impacted women adversely, these briefs also assess the gendered experience of the crisis, on the lives and livelihoods of women, including their physical and emotional well-being.

Home production, technology and women’s time allocation

The gender gap in time use, especially related to cooking and fuel collection, constrains women’s participation in remunerative activities, while also disproportionately having higher adverse health impacts for women. More efficient technology for home production—in the form of LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) usage for cooking—may enable women to invest the time and effort saved in more productive activities and thus increase their wellbeing. This aims inducing households to switch to LPG for cooking, through information campaigns on the health benefits of clean fuels and the existing LPG subsidy. It builds on the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, which seeks to expand access to clean fuel among rural households.

Impact of COVID-19 on urban poor in industrial clusters: a gender lens

As work opportunities in agriculture shrink, the future lies in improving women’s access to jobs in manufacturing and services. It is therefore, important to understand the demand and supply factors that determine their participation in these sectors. The project seeks to examine the profile and background of women workers in contemporary industrial and urban landscapes—types of opportunities available, barriers to participation, and aspirations and expectations from industrial employment. It further aims to situate the findings within the context of existing policy and regulatory frameworks, and the implications they hold for women’s industrial employment, while also assessing the impact of the pandemic on the lives and livelihoods of women.

Nudging households to increase the usage of clean fuel

Air pollution is a grave public health concern and cooking with solid fuels is a major contributor, which also has a disproportionately adverse impact on women. In this project, based in Madhya Pradesh, villages were randomly assigned to a campaign by public health workers to either raise awareness about health effects of solid fuels and mitigation measures, or health awareness on the LPG subsidy programme, or a ‘control’ group in which no information is provided. In the ‘health only’ intervention, households become more likely to have a smoke outlet or a separate cooking room, indicating that financial constraints and design of public subsidy schemes are salient in inducing regular usage of clean fuel.

Women in agriculture: gendered impact of mechanisation on labour demand

The trend of mechanisation in agriculture, which increased exponentially since the 1990s, has had an adverse impact of farm employment, especially that of women. When the production process is sequential and the division of labour across complementary tasks is gendered— as is the case in agriculture— technological change can have a differential impact on women’s and men’s labour. By constructing a comprehensive database of multiple secondary data sources on farm employment, agricultural inputs, climate and socio-economic characteristics at the district level in India, this study explores various aspects of the gendered effects of technological change in agricultural production.

Women’s Workforce Participation In India: Statewise Trends

In Andhra Pradesh, the rise in urban women’s work participation rates are exceptional. The state shows high incidence of self-employment among women in both rural and urban areas. However, almost 66 percent of such women in rural areas work as unpaid helpers in household enterprises. In the urban areas, the incidence of women’s entrepreneurship in self-employment is visible. Among wage workers, MGNREGA has been an attractive option apart from other construction, manufacturing and service employment. The urban areas show some diversity in women’s engagement, while in rural areas women work in agriculture, construction and low productive manufacturing sectors

Women’s Workforce Participation In India: Statewise Trends

Madhya Pradesh (MP) is the only state in India to have witnessed a rise in workforce participation rates (WPRs) of women in both rural and urban areas between 2011-12 and 2017-18. The increase in women’s WPR in MP was driven largely by increase in self-employment in the rural areas and regular employment in the urban areas. According to the Periodic Labourforce Survey in 2017-18, more than half of the female workforce in the state is self-employed, with a higher incidence of self-employment in rural areas. While approximately 88 percent of the rural self-employed women in MP are engaged in unpaid work, the share of women in own account enterprises is substantially high in urban MP. The distribution of casual women workers suggests very few women engaged under MGNREGA and other public works as 96 percent women in casual employment were engaged in non-public works, with very little security or guarantee of payment

Women’s Workforce Participation In India: Statewise Trends

Women’s labourforce participation rates (LFPR) reveals some interesting trends for Maharashtra. As per the figures from the labourforce surveys, the LFPR is significantly higher than the all-India figures, largely driven by higher than average rural employment. The state also shares a decline in self-employment and casual employment and a shift towards regular wage work for both rural and urban women. In Maharashtra the urban areas witnessed a consistent rise in regular wage work of women since 2004-05. More than 60 percent of women are employed as regular workers – 70 percent of which is concentrated in the services sector such as education, health and retail. In rural areas, the share of casual workers is considerably higher at around 42 percent, followed by 52 percent in self-employment. The incidence of unpaid family workers among self-employed women exceed 80 percent. While the urban areas show considerable diversity of women workers across occupations and sectors, women in the rural areas remain concentrated as manual workers in agriculture or within construction work.