How has India’s female labour force fared since Independence?

The current adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic notwithstanding, 73 years after its independence, India is considered among the economic powerhouses of the world. A recent report released by India’s Department of Economic Affairs suggests that even though downside economic risks remain, the worst may be over. This report also states that India’s future growth is likely to emanate from rural areas. However, for unlocking the full potential of India’s rural economy, the role and contributions of women in the rural economic landscape cannot be ignored, many of whom work unacknowledged as farm hands, as family helpers, as frontline service providers (anganwadi workers, ANMs and ASHAs), and who lead the millions of micro-enterprises started as part of India’s self-help group programme, bringing valuable income to their households.

Many studies conducted around the impact of the pandemic state that the social and economic implications of COVID-19 fall harder on women than on men. This makes the need of focusing on women and pushing the agenda of women’s economic empowerment more imperative, so they can help in picking up the threads and contribute to the rural recovery. In this article, we take a look at trends in women’s participation in India’s economy since the 1940s.

Slight improvement but still a long way to go

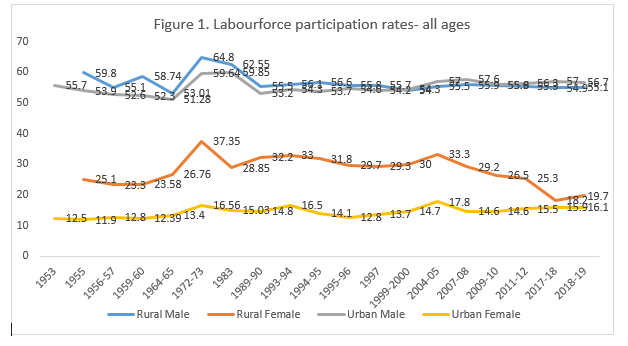

The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) recently released results of its Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for the year 2018-19. The estimates show a marginal improvement in overall labour force participation rates, more so for rural women (up from 18.2 percent in 2017-18 to 19.7 percent in 2018-19). Urban female labour force participation rates also show a modest improvement over the same period – from 15.9 to 16.1 percent. This seems a reprieve from the intense decline in female participation in the Indian economy, more so in rural areas, which has been the subject matter of many debates in the recent past. But what is interesting is that levels of female labour force participation now are significantly lower than those witnessed soon after India gained Independence (Figure 1). So what changed?

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI)

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI)

Before we get into the factors that may have accounted for a decline in women’s labour force participation over time in India – more so after the turn of the 21st century – it should be noted that the modest improvement suggested between 2017-18 and 2018-19 accounts for data only until the first quarter of 2019 for rural areas and the second quarter i.e. until June 2019 for urban areas. Many of us who have been tracking labour force participation rates since then know that a lot has changed, particularly after the COVID-19 shock. While the CMIE CPHS estimates provide more conservative rates of labour force participation (they use a stricter definition of who is in the labour force – only those who report offering themselves for work “on the day of the CMIE survey”, as opposed to those offering themselves for work for “at least one hour in any day of the week” during the PLFS survey), they suggest a steep decline in labour force participation since the PLFS 2018-19 round. While the labour force participation rate – aggregate for men and women – now stands at around 40.3 percent in June 2020, early estimates suggest that women have been hit harder. The men to women employment ratio deteriorated from 8.4 during 2019-20 to 9.1 during April-June 2020.

In fact, as figure 1 suggests, while urban female labour force participation rates have always been more or less stagnant (another sign of worry as India increasingly urbanises), rural female labour force participation rates have only worsened, hitting a high of around 37 percent in the early 1970s, and then again 33 percent in 2004-05, but then declining since.

Much has been written about the conundrum of declining labour force participation for women. It remains a puzzle as many of the barriers that would otherwise constrain women from taking up productive employment have reduced.

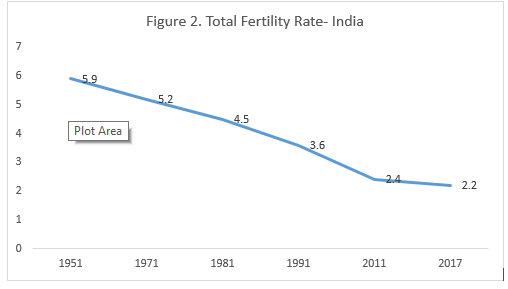

Fertility Rates

In 1951, the odds of a woman of reproductive age bearing children were very high (around 6 children). In 1981, the odds reduced, but were still considerably high – more than 4 children. By 2017, Indian women were only likely to bear 2 children.

Source: Data from Sample Registration System’s reports

Source: Data from Sample Registration System’s reports

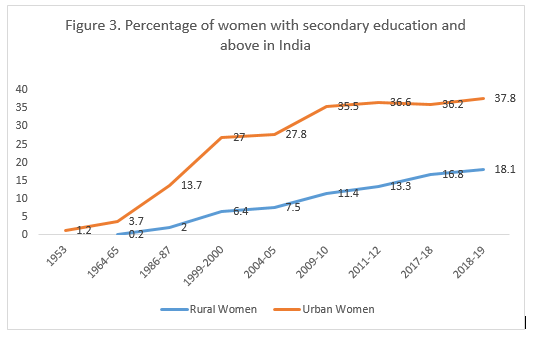

Rise in Secondary Education

While the percentage of women who have completed at least secondary level education or more has risen (Figure 3), particularly in rural India, that alone cannot be a reason for women not joining the labour force (because they are now in school). Surely, women who are now more educated, and fall on the rising part of the U-shaped association between secondary education and labour force participation, would want jobs? The NSS confirms this, with young women showing higher aspirations to participate in the labour market than their mothers. So what gives? For one, norms around chastity and early marriage still prevail. A girl in rural India is likely to be married early, if not before the age of 18, at least before she turns 22 (the average age of marriage for women in rural India is around 21.7 years). Two, appropriate jobs for more educated girls are not available, especially in rural areas. So girls drop out of the labour force even before they reach their productive years; their aspirations remain unfulfilled.

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

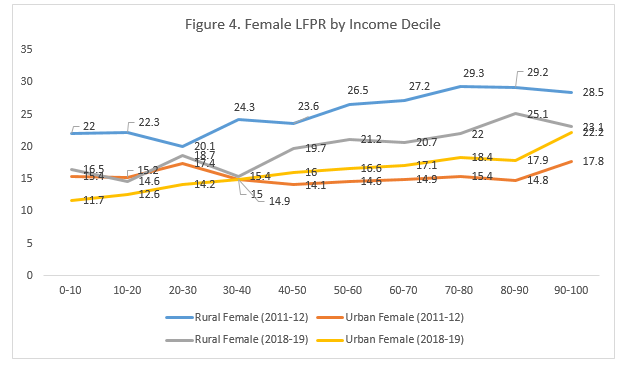

Income Effect

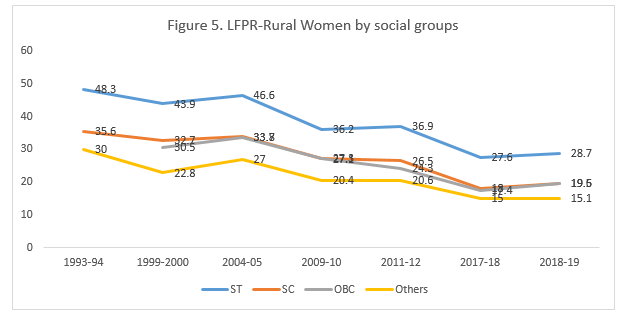

The income effect too does not explain the conundrum. In fact, women in higher income deciles show higher labour force participation rates (Figure 4). What constrains instead is social group membership, with women from higher caste categories reporting the lowest labour force participation rates, and more SC (Dalit) and ST (Adivasi) women stepping out for work, ordained perhaps by their more impoverished circumstances or less restrictive norms around mobility.

Source: Data from NSS Report no. 554 and Annual Report, PLFS 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: Data from NSS Report no. 554 and Annual Report, PLFS 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: NSS’s Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Social Groups in India reports for various years and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: NSS’s Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Social Groups in India reports for various years and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Under-reporting of Unpaid Work

The final explanation given for the abysmally lower labour force participation of women in India is under-reporting. Debates abound on what gets defined as women’s work, how the hours that women put in unpaid work needs to be accounted for, and why the standard modes of questioning on who gets included as being in the labour force might miss women working for a few hours each day as unpaid labour on family farms or enterprises. There are also explanations on how the PLFS rounds may not be comparable to the earlier NSS EUS rounds because of the sampling methods followed, and therefore much should not be read in the decline suggested in recent years.

Irrespective of these explanations, the fact remains that not as many women in a country of India’s size and income level, are working or are available for work. It is clear that it would take special effort both in devising more scientific methods to measure women’s labour force participation, and in providing more suitable job opportunities for them. The time to do so is now, before the unprecedented shock presented by COVID-19 further depresses women’s already grim work situation. Perhaps lessons may be drawn from the past, on what India did right in the early 1970s and 2000s.

Based on the entrepreneur profiles that emerged from our primary dataset, we have identified three customer archetypes or personas of women engaged in home-based businesses: millennial entrepreneurs, striving entrepreneurs, and latent entrepreneurs. These personas are based on the age, entrepreneurial and risk-taking abilities of entrepreneurs.

Based on the entrepreneur profiles that emerged from our primary dataset, we have identified three customer archetypes or personas of women engaged in home-based businesses: millennial entrepreneurs, striving entrepreneurs, and latent entrepreneurs. These personas are based on the age, entrepreneurial and risk-taking abilities of entrepreneurs.