Women’s control over their economic resources: Evidence from NFHS 5

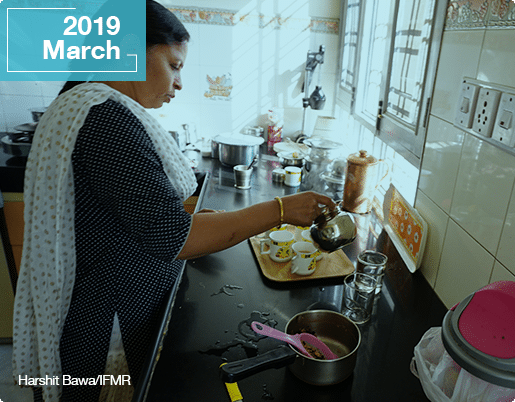

Economic violence refers to any act or behavior causing economic harm to an individual and generally involves coercive control of economic resources of a person . It is one of the many interconnected forms of violence often taking place at the domestic realm in the context of intimate relationships leading to adverse consequences on mental, physical, and financial well-being as well as other development opportunities of the victims and their dependents both in the short and long-term. This blog attempts to provide estimates of the incidence of economic violence in India based on the National Family Health Survey 5, conducted during 2019-21.

Although economic violence is now legally recognized in a few of the European Union member states like Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia and it is a commonly used tactic by perpetrators for coercive control over the victims and co-occurs with other forms of violence, it is less talked about and underreported. The under-reporting arises majorly due to the general lack of awareness about what constitutes economic violence. The gap in empirical understanding of economic violence and the factors influencing the occurrence of this form of violence also leads to a vacuum in the policy-making space through prohibitive measures to support the survivors.

There are majorly three types of economic violence categorized by the European Institute of Gender Equality: economic control which includes preventing, limiting, or controlling a victim’s finances and related decision-making; economic exploitation which means using the economic resources of a victim to the abuser’s advantage; and economic sabotage which involves preventing a victim from pursuing, obtaining, or maintaining employment and/or education. However, the identified indicators from NFHS 5 allows us to explore only the extent of economic control and economic exploitation experienced by women in India.

According to NFHS 5, 49% of women, aged between 15 to 49 years, don’t have the decision-making power on how to spend their own money. The situation is relatively better for urban women as compared to their rural counterparts since the share is relatively lower at 43% for urban women and 51% for rural women. This is because urban women face less restrictive socio-cultural norms and enjoy better agency as compared to rural women. Also, there exists vast state-wise variation when it comes to women’s control over their own money. The three states with highest shares of women with decision-making power over their own money, are Himachal Pradesh, West Bengal, and Karnataka with the shares being 62%, 61%, and 59% respectively, whereas the worst performing states are Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Assam with the shares being 32%, 29% and 28% respectively. The state-wise patterns indicate varying levels of women’s agency and the associated socio-cultural norms across the states.

The control over one’s own money also varies among women in different age-cohorts, with the control steadily increasing with age. While only 35% women in the age-cohort of 15-19 years can decide how to spend their own money, this share rises to 59% for women in the age-cohort of 45-49 years. As women transition from young adulthood to middle age, their growing social network often make them collectively empowered, help them challenge the restrictive social norms and exercise better agency. Moreover, financial distress has been a contributing factor to the prevalence of economic violence as 54% women in the ‘poorest quintile’ reported not having the control over their own financial resources. This percentage goes down among women belonging to upper expenditure quintiles.

The partner pay gap- the difference in earnings between the partners – turns out to be a significant influencer of economic violence as women’s relative earning position tends to determine the interpersonal power dynamics within the couple. Around 65% of women who earn equal to their husbands or more than their husbands, are found to have command on how they spend their own money, and the share is 59% for those earning less than their male spouses. The findings from NFHS 5 reveal a U-shaped relationship between women’s control over their own economic resources and their education level. This implies that women at very low levels of education have better command over their economic resources as compared to women in secondary/higher-secondary levels of education; the control increases for women with graduation/post-graduation levels of education. As NFHS 5 reveals, this too can be explained by the partner pay gap. According to the data, the share of women earning more or less similar to their male spouses is high among women with lower levels of education and thus on average they enjoy better command over their economic resources. Women at secondary/higher secondary levels of education, earn much lower than their spouses on average, leading to lower agency and less control on their own economic resources, and again the ‘partner pay gap’ declines for women with tertiary level of education, leading to better agency. Additionally, as the education levels of the male spouses increases, the females are found to enjoy more decision-making power over their own earnings as educated men are supposed to conform to more gender-equal norms. Approximately 50% of women whose male spouses received no education, don’t have any command over their own money. This share goes down to 36% for women with male partners educated above the secondary level.

Another commonly found example of financial abuse is the male spouse depleting the wife’s savings without her knowledge/consent. According to NFHS 5, around 44% of women stated that they have a bank savings account of their own, but they are not in control of the money in it. This share again varies by education levels, with the share being 44% for women without any education level and the share declining to 36% for those with education level above secondary level, reflecting higher agency among educated women.

Despite the pervasiveness of low agency of women when it comes to controlling their own incomes and financial resources, the recognition of it is lower. This lack of recognition is often due to not acknowledging the exclusion as another form of discrimination and assault on women. This points to the need for generating more evidence and awareness around the various forms of exclusion both in the legal and scholarly spheres. Criminalizing economic abuse would help to send a firm message about the unacceptability of this form of violence. Allocating significant budgetary resources for training legal professionals for increasing their capacity to recognize, investigate, and prosecute economic violence would be needed to address and prevent its occurrence. Along with this, the access to the services to combat familial violence must be provided to its victims too. Lastly, we need more sophisticated surveys capturing the various dimensions of economic violence to fully comprehend the subject.

This blog is written by Aneek Choudhury, Research Associate and Bidisha Mondal, Research Fellow at IWWAGE.

Picture credit: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment

- Posted In:

- Latest Blogs

Leave a Reply