Gender Gap in Private School Enrolment Reiterates Gendered Investment by Households on Education

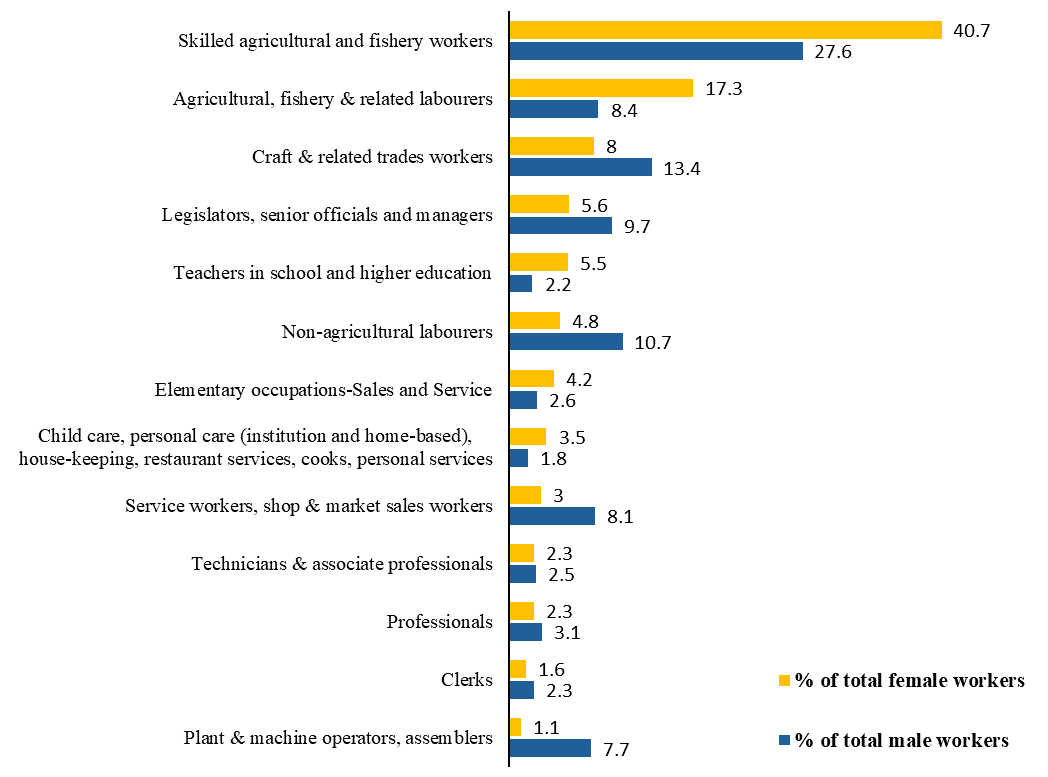

India experienced a steady rise in private school enrolment post 2015, both in absolute numbers and as a share of total enrolment. After a moderate dip during COVID-19, the share started rising again from 2022-23. A parallel trend has been the persistent gender-gap in private school enrolment shares- greater proportion of boys being enrolled in private-unaided schools as compared to girls, and the gap remaining almost similar in the last five years. At the national level, 33 percent girls were enrolled in private schools as compared to 39 percent boys during 2023-24, according to latest statistics released by UDISE Plus. The private school enrolment shares were high for both boys (72 percent) and girls (68 percent) at the pre-primary level, resulting in a lower gender-gap of 4 percentage points (Graph 1). At the primary and upper-primary level, the share of enrolment in government and government-aided schools increases substantially, alongside an increase in gender gap in private school enrolment. At secondary and higher secondary levels, while private school enrolment increases for all students, the gender gap persists at 6 to 7 percentage points with boys having a higher representation compared to girls. Additionally, these differences are much starker in certain states than the national average of 6 percentage points, and often increases with levels of education. Gender gap in private school enrolment is an effective indicator to reflect households’ preferences in investment on children. What do these preferences reflect? What could be the possible reasons behind this trend?

Graph 1: Share of enrolment across types of school management for different levels of education, by gender, All India, 2023-24 (%)

Source: Report on UDISE Plus, 2023-24, Ministry of Education, Government of India. Link: https://udiseplus.gov.in/#/en/page/publications

Source: Report on UDISE Plus, 2023-24, Ministry of Education, Government of India. Link: https://udiseplus.gov.in/#/en/page/publications

A deep drive into the states, highlights considerable variations either in terms of gender-gap in overall private school enrolment or its variation across levels of schooling. For instance, while the gender-gap in preference for private schools is relatively higher in Delhi, it does not vary much by level of schooling and ranges between 8 to 9 percentage points across all levels of schooling. On the contrary, the gender-gap in share of private school enrolment increases alongside increase in level of school education in Tamil Nadu from 4 to 9 percentage points between primary and higher secondary. Similarly, in Rajasthan where almost one-third of total schools are private-unaided, there is an even starker rise in gender gap in private school enrolment from 9.3 percentage points at primary to 12.6 at upper-primary and 14.3 at secondary levels. Thus, in certain states, preference for private schools for boys is much higher at secondary and higher secondary levels than at elementary. This trend reiterates that when costs of education become higher, households tend to invest much more in boys than in girls. In contrast, gender gap in private school enrolment is negligible in Kerala across all levels of school education. Moreover, the share of private school enrolment declines with increasing levels of school education. This indicates not only equity in access to school education in Kerala, but also preference for government schools especially at secondary level.

It is important to emphasize that private school education may not always be synonymous with good quality education. Therefore, parents’ willingness to spend more on the education of boys by sending them to private schools might not always result in greater returns in future. A considerable proportion of private schools in India fall under the so-called ‘low-fee’ category that primarily cater to the low-income families. Some of the characteristics of private schools that attract parents include English being the medium of instruction, focus on measurable outcomes and perceived quality. However, extensive focus of the low-fee private schools on cost efficiency and learning outcomes without adequate focus on holistic development of children and teacher training, is a cause of concern regarding the quality of education.[1] Past research has highlighted that many low-fee private schools neither provide quality nor confer status.[2] Another study focusing on low-cost private schools in Delhi and NCR, primarily attended by children from economically disadvantaged families, observed poor learning achievement in English language at primary level. This deficit negatively impacted children’s ability to comprehend other subjects as well.[3] On the other hand, while thin spreading of State resources to conform to increasing demand for education, has to some extent, negatively impacted the quality of public education in many states in India, government schools are mandated by the RTE Act, 2009 to adhere to guidelines for holistic child development, social justice, inclusivity and to ensure last mile accessibility. Therefore, government schools can impart both good quality education as well as holistic development of children, if managed well. States such as Delhi and Kerala are notable examples with government schools accounting for a significant share of overall school enrolment.

Sending a child to a private school demands considerably higher out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures from households since per-child costs are much higher in private than in government schools. Therefore, a higher proportion of boys in private schools indicates greater investment in education of boys than of girls by households. Since the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009 mandates free elementary education in government schools, households’ OOP expenditure per student in government schools is minimum at elementary level, and mostly spent in private tuitions or conveyance. In comparison, average per student expenditures in private-unaided schools at primary and upper-primary levels were higher than those in government schools by 11 times and 8 times respectively, as per estimates from latest data available for 2017-18 from NSSO’s household survey on education.[4]As children transition from elementary to secondary grades, while OOP expenditures increase across all types of schools, the rise is much steeper in private-unaided. For instance, average per-child expenditure at higher-secondary level in a private school in India during 2017-18, was almost four times higher than that in government schools (Rs. 7006 in government schools vs. 25,858 in private schools during 2017-18).

Past research suggests multiple reasons behind gendered human capital investment. Prevailing socio-cultural norms around gender play an overarching role. Overall differential treatment of sons and daughters predominantly stems from social norms, resulting in discrimination of girls across multiple aspects including investment in education.[5] Education is seen as an investment that yields future returns which is comparable to other investments .[6] Primary reasons cited by Indian parents behind preference for private schools as reported by UNESCO during 2021-22 were: perception of better quality, English as a medium of instruction, and private schools being a marker of higher status in society.i These characteristics are believed to improve an individual’s future employability as well. However, pecuniary incentives to invest in women’s education are believed to be less as most women either join the workforce in smaller numbers or exit sooner, which adversely impact financial returns. Gordan (2021)[7] who studied shifts in mother’s aspirations for their daughters’ education, found a complex interplay between economic factors and shifting socio-cultural norms. Although the gender gap in educational investments was found to have reduced over time, it was still found to be prevalent especially in rural areas. Foster & Rosenzweigh (2001)[8] located the practice of patrilocal exogamy–women marrying men from different villages and moving in with their husband’s family– limiting the economic benefits that parents can gain from investing in their daughters’ education. Also, the social costs of women working may outweigh the financial benefits for households, thus reducing the likelihood of parents investing in their daughters’ education. More importantly, societal expectations for women to be the primary caregivers still govern household decisions with regard to investment in education.

The persistent gender gap in private school enrollment in India, particularly above elementary level, reflects a broader pattern of gendered investment in education by households driven by socio-cultural norms and expected pecuniary returns in future. While boys are prioritized in terms of access to private schooling, especially as the financial costs of education rises at higher levels, girls often face constraints due to societal expectations around their roles and the perceived lower returns on investment in education. Regional variations further complicate the picture, with certain states showing a more pronounced gender gap, indicating greater prevalence of gendered social norms. Overall, addressing the disparities in quality of education across both private and public schools is the need of the hour, to ensure equal access to good quality education to students irrespective of their gender and across socio-economic strata.

This blog is written by Mridusmita Bordoloi, Economist at IWWAGE, Sharati Roy, Research Associate at IWWAGE

Footnotes

5. Rashmi, R., Malik, B. K., Mohanty, S., Mishra, U. S., & Subramanian, S. V. (2022). Predictors of the gender gap in household educational spending among school and college-going children in India. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications. https://www.nature.com/

7. Gordan, R. (2021). Your mind becomes open with education’: exploring mothers’ aspirations for girls’ education in rural Bihar. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. https://www.tandfonline.com/