Why do women depend less on informal sources for job search than men?

The latest PLFS round reveals that job search methods differ between men and women with women relying more on formal sources of job searches than men. The formal job search methods include applying to prospective employers/places, answering job advertisements, checking at factories, and work sites, registering with employment exchanges, and registering with private employment centres. In contrast, informal sources comprise personal networks, including relatives and friends. According to PLFS 2021-22, 76% of unemployed men are looking for a job through formal channels, whereas 87% of unemployed women, a much higher share, are resorting to formal sources for the job search. 20% of unemployed men are using their informal networks to find a job, and the share comes down to a much lower 12% in case of women. The rest of the unemployed are either seeking finance for starting a business or applying for a permit to start a business. This blog explores the reasons behind women’s preference for formal sources for job search over informal ones.

Informal networks, as a social resource in job search, provide access to more valuable information which are unavailable through formal means. As a result, informal networks are often more efficient to navigate individuals into better job matches with higher job satisfaction and earnings more quickly. PLFS data corroborates this view of network efficacy as it is observed that women searching for a job through informal sources face a shorter duration of unemployment than those depending on formal sources. Among the unemployed women currently looking for a job through a formal source, more than 30% women face a spell of unemployment of more than 2 years and for 18% women, the duration of the spell of unemployment has been more than 3 years at that time of survey. On the other hand, only 15% of the unemployed women who use the informal sources for job search, had a duration of a spell of unemployment of more than two years, and only 8% of them faced a spell of unemployment of more than three years.

Despite informal networks being more effective, women depending more on formal job search methods as compared to men, have several causes and implications. Informal networks are powerful for job-hunting when they can grant access to a more heterogeneous set of people, located in various sectoral and occupational positions. With the diversity of people in network, the non-redundancy of job information and the effectiveness of one’s network rises. Also, with higher socio-economic status of one’s informal contacts, the chances of receiving information about highly paid jobs, jobs in higher social stature, increase. However, the composition of women’s informal network is often found to differ from men. With a much higher share of family responsibilities and less participation in the workforce, women have limited exposure to diverse group of contacts. Marriage further limits their informal connections due to the cultural restrictions preventing freedom of interactions with outsiders. Also, with gender homophily i.e. the preference of interactions with persons of their own gender, the informal networks are often gender-segregated with women’s network being predominantly consisting of women only. Additionally, due to the existing gender-based segregation in the labour market, women’s presence is low in high-wage, high-skill sectors and occupations. Thus, in a gender-segregated network, women get limited access to information about the high-skill, highly-paid jobs. These factors together explain why fewer women in comparison to men, find their informal network to be effective for job search and majority follows the formal search methods. However, women who had worked previously tend to depend on their informal network more than those who never worked as often due to the exposure associated with their work experience they tend to have more diverse informal contacts and an effective source of information for job opportunities.

As placements through informal routes often tend to reinforce the existing gender-based occupational and industrial segregation, women with higher education depend more on formal sources in an attempt to escape the trap of female ghettoization in low-paid jobs. The PLFS data reveal that among women without any literacy, 48% depended on informal sources, with the dependence coming down to 17% for women with primary and below primary level of education, 22% for women with middle to higher-secondary level of education, and only 8% for women with graduation and post-graduation level of education. For the urban areas, women with basic and intermediate level of education depends relatively more on informal networks as compared to their rural counterparts. This indicates that for the semi-skill occupations, women’s informal network is relatively more effective in urban areas than rural areas. But again, for women with education level of graduation, post-graduation and above, the dependence is very less on their informal network in both rural and urban areas. Although for men too, the reliance on the informal network gets reduced with increase in education level, the decline is starker for women. This diminishing dependence on informal network for more educated women aspiring for better paid white-collar jobs appropriate to their education levels, points towards their gender-segregated informal network as a less effective source of information.

However, as revealed by the PLFS data, even among the highly educated women, expectedly looking for high-skill, highly-paid jobs, those who have dependable informal network and thus explore that, face a shorter spell of unemployment as compared to those who depend on formal sources. Among women with education level of graduation, post-graduation and above, around 30% women faced a spell of unemployment of more than two years and 17% are looking for a job for more than three years, as they depended on formal sources of job-hunting. On the other hand, only 16% faced a spell of unemployment for more two years and only 5% for more than three years when these highly qualified women looked for jobs though informal sources. This indicates that informal networks when can be depended on for high-skill jobs too, can be more effective as compared to formal sources.

The findings from PLFS indicate the need of recognition of the lack of social capital for women and their exclusion from male-dominated influential informal ties and networks. Women are not a homogeneous group and there exist many other cross-cutting socio-economic factors among them determining their reach to the informal contacts instrumental to gender-balanced jobs. Even after considering these factors, women across all sections are in a disadvantageous position. This is majorly due to the gendered nature of social network and women’s poorer structural location in the jobs market ladder. With the job search method often playing a crucial role in reinforcing the existing gender-based occupational and industrial segregation by leading to women’s concentration in women-dominated jobs, few measures on part of the government and Civil Society Organisations might prove helpful. For example, developing strategies to form networking groups that will help women establish the right connections by making ‘women in powerful positions’ a part of these groups; sensitisation about the often consciously created resistance to women’s integration to the influential network, might be undertaken to address these concerns at least partially.

Author: Bidisha Mondal is a Research Fellow at IWWAGE.

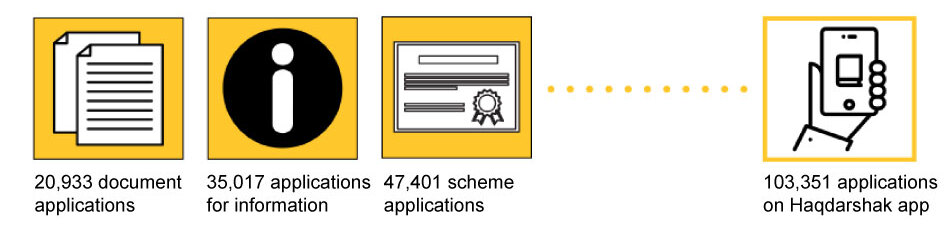

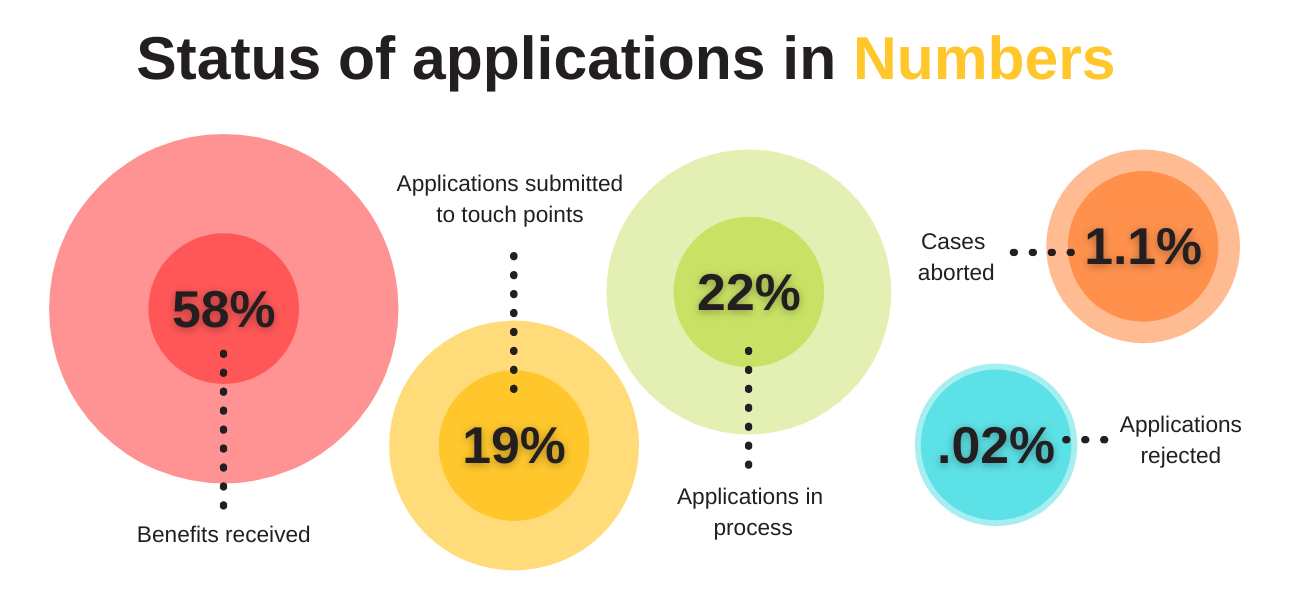

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

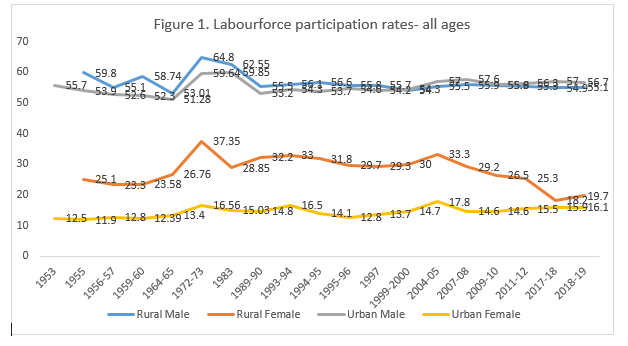

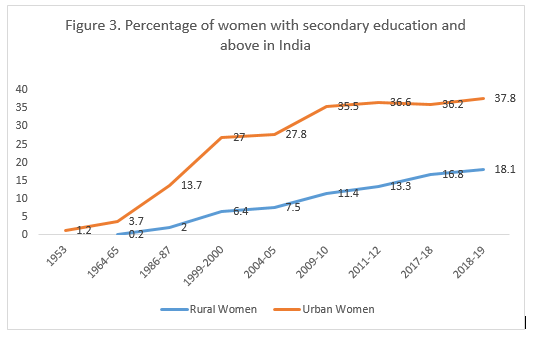

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI)

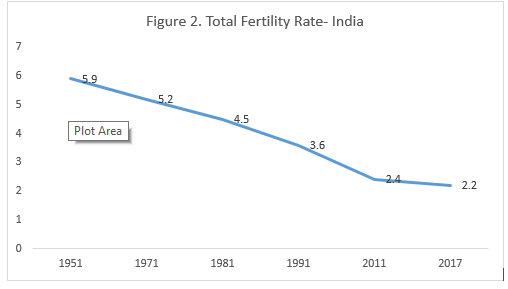

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) Source: Data from Sample Registration System’s reports

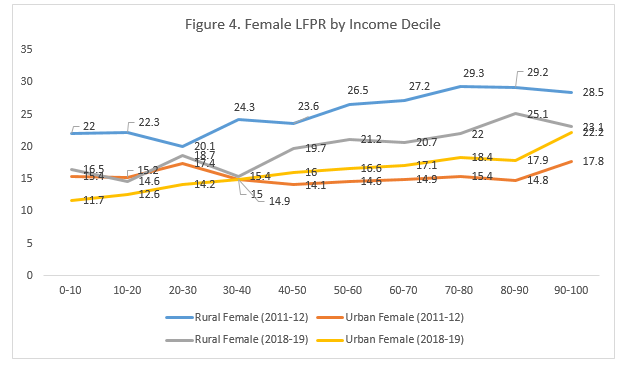

Source: Data from Sample Registration System’s reports Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: Data from published reports of NSSO’s employment-unemployment surveys (EUS) and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi Source: Data from NSS Report no. 554 and Annual Report, PLFS 2018-19 by Mospi

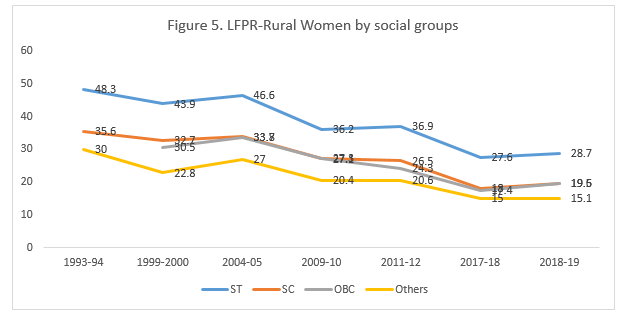

Source: Data from NSS Report no. 554 and Annual Report, PLFS 2018-19 by Mospi Source: NSS’s Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Social Groups in India reports for various years and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Source: NSS’s Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Social Groups in India reports for various years and Annual Reports of PLFS 2017-18 and 2018-19 by Mospi

Based on the entrepreneur profiles that emerged from our primary dataset, we have identified three customer archetypes or personas of women engaged in home-based businesses: millennial entrepreneurs, striving entrepreneurs, and latent entrepreneurs. These personas are based on the age, entrepreneurial and risk-taking abilities of entrepreneurs.

Based on the entrepreneur profiles that emerged from our primary dataset, we have identified three customer archetypes or personas of women engaged in home-based businesses: millennial entrepreneurs, striving entrepreneurs, and latent entrepreneurs. These personas are based on the age, entrepreneurial and risk-taking abilities of entrepreneurs.