Wage employment for women: Forgotten priorities

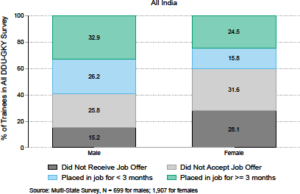

Low and declining women’s labour force participation rates in India have been a longstanding concern. Government policies for addressing this challenge have mainly emphasised promoting entrepreneurship among women. Designing skill development programmes (DDU-GKY, PMKY and so on) which also aim at building women’s skills to access technology; facilitating access to digital platforms and promoting partnerships with start-ups aimed at providing women with fintech solutions; and facilitating access to credit through extending low-value MUDRA loans have been some of the main interventions. All these programmes primarily aim at making entrepreneurs out of women as a way to achieving greater workforce participation of women – with a lateral objective of enhancing ‘Make in India’ efforts through greater entrepreneurial ventures by women.

But data on entrepreneurship of women in India suggest that there is a long way to go. The economic census, last published in 2013-14, showed that women’s enterprises were only 13.8 percent of total enterprises and 84 percent of these were operating without any hired workers. The average employment per women’s establishment was 1.67 workers indicating low employment creation capacity. Further, 27 percent of all non-agricultural establishments owned by women were operating from home – of which more than 50% were in manufacturing.

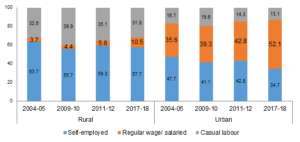

The periodic labour force survey (PLFS), 2017-18, shows that 52 percent of women’s workforce is in self-employment, which can be further disaggregated into three sub categories – own account enterprises (OAE), employers and unpaid/contributing family workers. The first two categories capture women’s entrepreneurial ventures best. Almost 32 percent of all women workers are engaged as unpaid helpers in household enterprises and only 19 percent run OAEs. These figures, coupled with micro-evidence from literature, show that the women OAEs remain trapped in low-scale, low-productive, low return ventures such as in rolling bidis and agarbattis, making pickles and papads, or mending clothes with a sewing machine.

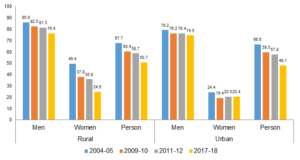

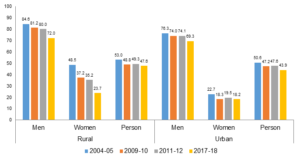

But self-employment only captures one half of women’s work. According to the PLFS, 48 percent women are in wage employment. Of these, 21 percent are in regular employment and 27 percent work in casual labour. The impact of increasing wage employment on women’s empowerment is well-established. Still, there is no policy emphasis for this sector.

There are several mechanisms that can be employed to increase women’s wage employment opportunities. For example, the MGNREGA attracts a large number of women, with about 55 percent of total person-days of work created under this legislation accruing to women. There are a number of field reports to suggest that provision of equal wages for men and women, proximity of workplace, assumed safety at workplace and so on, makes MGNREGA a popular option for women. MGNREGA has the potential to attract even more women if all its provisions such as creche facilities, shade and water are also provided adequately. Unfortunately, the trend of provision of work under this scheme has been stagnant and there have been challenges of delayed wage payments.

Outside of agriculture, where the absorption of labour has been declining, women are attracted to jobs in providing public services. The PLFS data show that 29 percent of women working outside agriculture in rural areas are engaged in public employment. Large numbers work as frontline workers, particularly in public health and education. Some cadres such as anganwadi workers and helpers, mid-day meal cooks, ASHA workers, ANMs are exclusively women (estimated to be over 60 lakh). Nearly half of the total teaching workforce in elementary education in India are women. In recent times there has also been an increase of women employed as police constables in many states. But despite these opportunities, women remain concentrated at lower levels of the occupational hierarchy, mostly restricted to what are seen as ‘women’s roles’ (traditionally caregiving occupations). They receive low wages and work in poor conditions.

An agenda of universal provision of basic services such as health, education and social protection can not only contribute towards improving India’s human development indicators but also create millions of new jobs, more so for women. Some state governments have provisions such as reserving posts for women in government jobs. But such measures can have an impact only when there is an expansion in the total number of government jobs. Having said that, there is a need to hire more workers for public services, given the millions of vacancies that exist for these posts as per government norms.

An agenda of universal provision of basic services such as health, education and social protection can not only contribute towards improving India’s human development indicators but also create millions of new jobs, more so for women. Some state governments have provisions such as reserving posts for women in government jobs. But such measures can have an impact only when there is an expansion in the total number of government jobs. Having said that, there is a need to hire more workers for public services, given the millions of vacancies that exist for these posts as per government norms.

Apart from casual wage work and regular public employment, women’s wage work includes work undertaken in factories, especially in garments, electronics and food-processing which have served as traditional sectors of women’s employment. While great emphasis has been on promoting ‘Make in India’, policies related to incentivising these sectors have been elusive. Recent subsidies announced for the textile sector aimed at generating employment are yet to show results.

Governments can push for multiple policies to create decent wage work opportunities for women, from expanding public works programmes such as the MGNREGA, to adding a cadre of public service para workers, for whom there is a crying need. Such interventions along with a focus on labour intensive manufacturing sectors can not only create employment and demand but also contribute to lifting the Indian economy out of its current economic slowdown.

This opinion piece is written by Dipa Sinha and Sona Mitra. Dipa Sinha teaches Economics at Ambedkar University, Delhi, and Sona Mitra is the Principal Economist at Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy (IWWAGE), an initiative of LEAD at Krea University.

This approach and the ability of women to meet to discuss their needs and put forth their requirements, is likely to be put to test on account of COVID-19. SHG meetings have traditionally formed a space for women to gather mutual support and raise their grievances. They serve as an important platform for women to share their lives and aggregate for a common cause. They have been the fulcrum around which well-known movements such as the anti-arak (alcohol) movement in Andhra Pradesh have gathered force; and around which the Scheduled Caste women in states like Punjab are mobilising to collectively farm common lands. Such mobilisation will suffer if women are not permitted to meet.

This approach and the ability of women to meet to discuss their needs and put forth their requirements, is likely to be put to test on account of COVID-19. SHG meetings have traditionally formed a space for women to gather mutual support and raise their grievances. They serve as an important platform for women to share their lives and aggregate for a common cause. They have been the fulcrum around which well-known movements such as the anti-arak (alcohol) movement in Andhra Pradesh have gathered force; and around which the Scheduled Caste women in states like Punjab are mobilising to collectively farm common lands. Such mobilisation will suffer if women are not permitted to meet.