IWWAGE-Institute for What Works to Advance Gender Equality

Opportunities for Transformative Financing for Women and Girls

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, women and girls in India have faced disproportionate economic and social impacts-ranging from job losses and depleted savings to increased unpaid care work and heightened vulnerability to violence. Recognising the urgent need for a gender-responsive recovery, IWWAGE and The Quantum Hub (TQH) hosted a pre-budget consultation on 1 October 2020 to inform the Union Budget 2021-22.

The consultation brought together experts to identify key policy priorities for advancing women’s economic empowerment. Drawing on these discussions, the resulting policy paper outlines actionable recommendations across four key areas:

– Expansionary fiscal policies to finance priorities for women and vulnerable groups

– Strengthening gender-disaggregated data and evidence

– Enhancing institutional mechanisms for gender budgeting

– Sector-specific investments in women-focused programmes

The paper also highlights relevant ministries responsible for implementing these recommendations, with the goal of ensuring a more inclusive and resilient recovery for all.

Impact of Covid-19 On Working Women

The Indian economy has been plunged into severe economic uncertainties created by the global pandemic COVID-19. At the same time, there are also discussions on how the eruption, the spread and the aftermath of the novel virus will affect women. The numbers of women at work, their sustenance at the workplace, their pay, their career graph was already a matter of grave concern and a much-discussed global issue. Now, in light of the COVID-19 scenario, the following questions become imperative to address: Are we foreseeing worse days ahead? What has been the impact of COVID-19 on working women, both in urban and rural areas? Which are the sectors where women have become dispensable? How do we ensure that women are not further marginalised in these unprecedented times? To answer these questions, one must start by analysing the data and underlying trends of women’s employment in India, including in sectors where they tend to be employed. We also need to scrutinise the long run repercussions the economic fallout of the pandemic will have on gender equality, both during different phases of the lockdown and thereafter. This note attempts to deliberate upon the aforesaid issues and reflects on some measures that can help bring about recovery and resilience for women.

Making a Gender Responsive Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme

The pandemic and subsequent lockdown measures in India have taken a toll on all aspects of life, particularly on livelihoods. While job losses have been observed in both rural and urban sectors, recent figures show that there has been an increase in creation of non-salaried jobs in rural areas, but generation of wage employment in the urban sector has remained a challenge. Over 21 million salaried jobs have been lost in India (out of a base of 86 million overall salaried jobs) between April and August 2020. This evidence points to the fact that urban livelihoods have taken a huge hit due to the COVID-19 crisis, and the ability of the urban sector to create new jobs to compensate for these losses is currently under a cloud. Women have been disproportionately affected by job losses. A recent report tracking the pandemic’s influence on informal work in India suggests that more women were out of work post-lockdown compared to men. Given the largely positive effects of MGNREGA on women workers, many policy experts have recommended designing and implementing an urban employment guarantee programme to alleviate the problems faced especially by urban women workers, particularly those in the informal economy. Recognising such a need for support in urban areas, various state governments have stepped in with their own urban employment guarantee schemes. The details of these schemes are provided in the brief.

Strengthening Socio-Economic Rights of Women in the Informal Economy: The SEWA Approach in West Bengal and Jharkhand

Women working in India’s informal sector face several vulnerabilities and are often denied decent working conditions and wages. This further exacerbates inequities and pushes them towards high risk poverty. The situation is worse for women belonging to socially disadvantaged castes and communities. Evidence from India and other contexts shows that the working poor in the informal economy, particularly women, need to organise themselves to overcome the structural disadvantages they face. Organisation gives these otherwise marginalised workers the power of solidarity and a platform to be seen and heard by decision makers with the power to affect their lives.

Since 1972, the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) is working as an organisation of poor women workers and a movement to create better alternatives. SEWA is currently operative in many states across the country and has a membership base of nearly 2 million women workers in the informal economy, comprising domestic workers, street vendors, agricultural workers, construction labourers, salt workers, beedi and papad rollers and such other vulnerable categories. SEWA’s programme in Jharkhand and West Bengal aims to increase the collective bargaining strength of women, particularly those working as agricultural workers, domestic workers and construction labourers (in the former state) and female beedi rollers in West Bengal. The programme aims to improve women’s access to and understanding of basic services, such as health and sanitation, and also increase their ability to demand local accountability through nurturing of grassroots leadership. The study tries to understand the impact that various components of its programme have had on informal women workers in Jharkhand and West Bengal. The women included in the study were predominantly engaged in beedi rolling, domestic work, construction work, agriculture and street vending.

Social protection through a digital tool reaches the milestone of 100,000 applications

“Living in a tier-2 city in the state of Rajasthan in India, I had to take half a day off from work to apply for an Aadhaar card. I had to travel to the Aadhaar center, which was about 7kms away, stand in line for one hour for my turn to come, only to realize that the machine was not accepting my iris scan. The three officials at the center could not figure out the problem, after struggling for 20 minutes. I was told to wait for another half hour, for the machine to start working. After half an hour, the machine started working and my application was submitted. The entire process took 4 hours. The majority of people living in rural areas do not have the luxury to step away from their work and lose out on daily wages.

The time spent on this process can be minimized for government entitlements that require in-person presence of the applicant and eliminated for entitlements that do not require the in-person presence of the applicant” – Anoushaka

Poor households often rely on government entitlements for mitigating risk and livelihood development. With the aim of increasing information about and uptake of government entitlements, and with the support of the State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM) in the state of Chhattisgarh, IWWAGE – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University, and Haqdarshak Empowerment Solutions Private Limited (HESPL), is implementing a project for promoting government entitlements through women self-help group (SHG) members as agents. As part of this project, self-help group (SHG) members receive training on how to use a digital application, Haqdarshak, which provides a ready reference of more than 200 central and state government welfare programs, their benefits, eligibility criteria, documents required, and the application process for each scheme. The trained agents offer door-to-door services to their respective communities using the app to support households to gather information and apply for government programs, for a small fee.

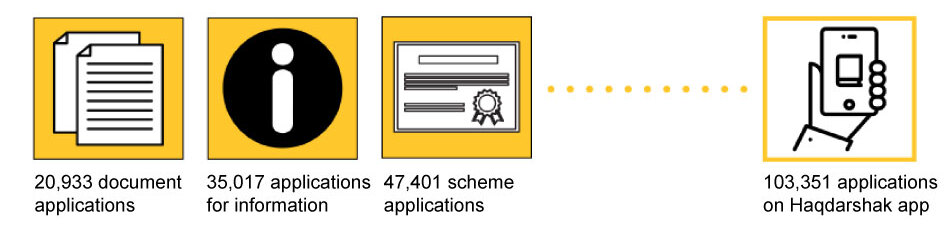

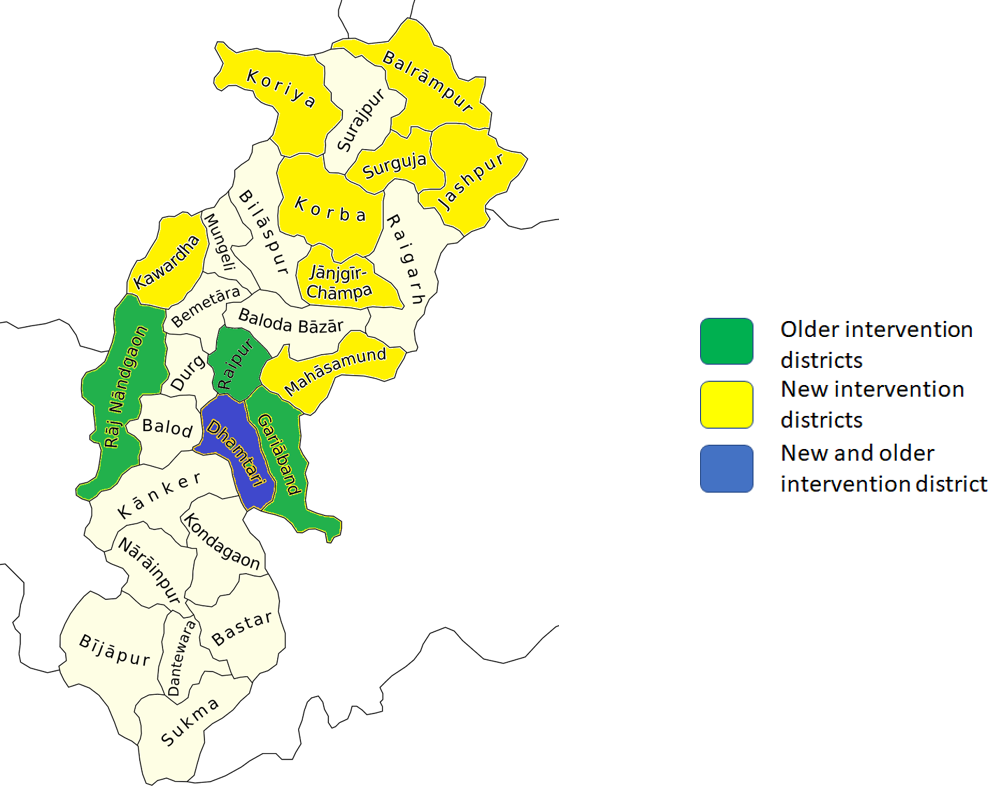

The project is being implemented in four districts of Chhattisgarh (Raipur, Rajnandgaon, Dhamtari and Gariyaband) and over the past year around 2,700 SHG women have been trained to become Haqdarshak agents. Among all of the trained women around 1,000 performed their duty actively and have received over 100,000 applications for a wide range of government entitlements[i].

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

A deep-dive into these 100,000 applications reveals several interesting trends:

- 34% of the total applications are for COVID-19 related informational schemes. These include availability of free ration at PDS shops, cash transfers to women PMJDY account holders, distribution of free food packets for children enrolled in government anganwadis, and availability of free gas cylinders under the Ujjwala Yojana. Providing information to the rural poor about the availability and the mode of access for these additional benefits is an important step in ensuring that the benefits reach the intended beneficiaries. In such situations, the Haqdarshika’s role was to inform citizens enrolled in these schemes of the additional benefits available they can avail and, when necessary, support them to access these benefits.

- PAN cards are the most sought-after document, accounting for 80% of the total applications for documents. Insights from our fieldwork suggest that people in rural areas perceive the PAN card as a document required for opening of bank accounts and it is also promoted as such by many application touch-points.

- Among welfare schemes, insurance programs like the Pradhan Mantri Bima Suraksha Yojana (PMSBY), Ayushman Bharat and Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) are the most popular schemes among applicants.

Among the four districts in which the program was implemented, Raipur district accounted for around 48% of the 100,000 applications, followed by 38% from Rajnandgaon, and the remaining 14% of the applications were from the Dhamtari and Gariyaband districts. However, an important caveat is that the program targeted Raipur district first, which means that the intervention has been running in the district for a much longer time. The intervention has also targeted fewer blocks in Dhamtari and Gariyaband, as compared to Rajnandgaon and Raipur districts.

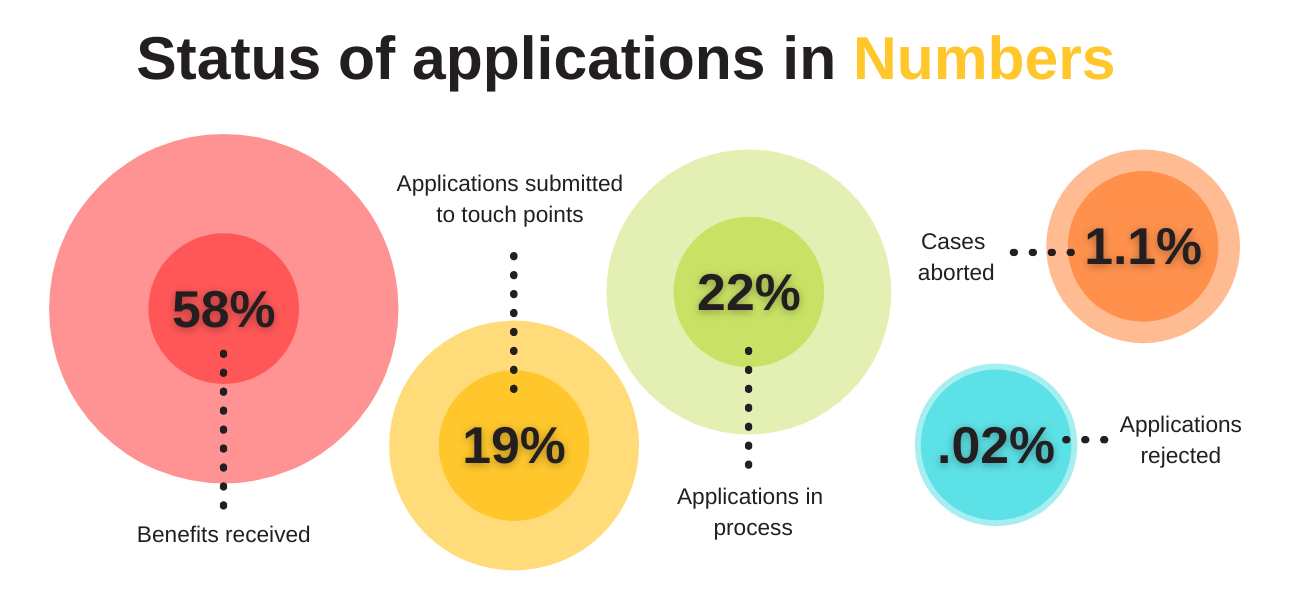

Reaching the 100,000 applications mark on the Haqdarshak platform has been an important milestone for the project. However, there have been several challenges in implementation along the way and the program team is working towards developing solutions to address these.

Dropout of Haqdarshikas from the program

Of the 2,700 women trained to be Haqdarshikas, only 603 are active as of September 2020. A Haqdarshika is considered ‘active’ if she has processed at least one application in a given month. Some of the factors which may account for this trend are:

- Some of the training participants might not pass a post-assessment test, which is required to conduct transactions on the platform.

- 60 to 80 percent of the agents drop out after the fourth month of activity. This could be due to saturation of applications for schemes and documents for which Haqdarshikas (HDs) have most information. Refresher trainings are being conducted with HDs who dropped out of the program, to overcome this challenge.

- Other reasons include damages to their smartphone, shared usage of smartphone resulting in non-availability of the phone for the Haqdarshikas, restrictions on mobility from their families, lack of entrepreneurial spirit etc. This is clearly an issue of targeting. Selecting suitable candidates for the training requires time and effort, since potential participants need to be screened against certain minimum requirements and informed about the expected commitment, type of work, and remuneration of the program. Ensuring greater buy-in and providing a higher degree of support to local government officials is essential to make any progress on this issue.

Long processing time for applications

While the 100,000 applications milestone suggests that there is a high demand for government entitlements among rural households, not all the applications have translated to benefits received by the citizens. This could potentially be explained by the long processing time and procedural delays for certain schemes and documents. The project team is exploring ways to delve deeper into the reasons for delay and also ways to tackle this challenge.

Technology needs a sustained value proposition

Another reason why we see less than 100% conversion of applications submitted to benefits received is that Haqdarshikas at times do not update the status of the application itself. This indicates that while the citizen may have received the benefit, the status displayed on the app shows that the application is ‘pending’. This could be due to the fact that Haqdarshikas do not follow up on the processed applications in a timely manner or to the citizens not feeling comfortable providing proof of receipt of the document or scheme they applied for due to privacy concerns. Both instances point to a lack of practical and/or material incentives to update the status of the applications, besides the Haqdarshikas’ own diligence. This issue could be addressed, for example, by a change in the remuneration structure of the model or by increased integration of the app in the government’s own application system, thus reducing the need for manual inputs.

In the coming months, the Haqdarshak program will be scaled up to 21 different blocks in nine additional districts of Chhattisgarh. In these blocks, with the support of CGSRLM, the implementation will focus on Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) and Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) to improve their access to information and in turn, government entitlements.

[i] [i] These applications were received between June 2019 and September 2020.

Anoushaka Chandrashekar is a Project Manager with LEAD at Krea University and Raka De is a Research Associate with LEAD at Krea University.