Undoing Unpaid Work: Tackling Time Poverty is Key to Address Gender Inequality

A recent announcement from a political party in Tamil Nadu has pushed forward frequently halted debates around recognizing women’s unpaid work. The party promises to pay housewives a monthly wage to recognize and support their household work. This announcement has come at a crucial juncture as the world adapts to a ‘new normal’, unfortunately the burden of this new normal is falling disproportionately on women in different ways. These unprecedented times precipitated by the COVID19 crisis have unfolded new layers of the gendered dimensions of unpaid care work. It has deepened pre-existing gender inequalities, increased women’s economic and social insecurity, domestic violence, unpaid care work, and also disconnected them from availing institutional and social support (UN Women 2020). Due to the closure of schools and families at home, women’s care work increased by 30% during COVID19 (Khan and Nikore 2020). The pandemic has shown that women bear the brunt of ‘disproportionately divided domestic duties’ which points to the larger issue of the gendered nature of unpaid work.

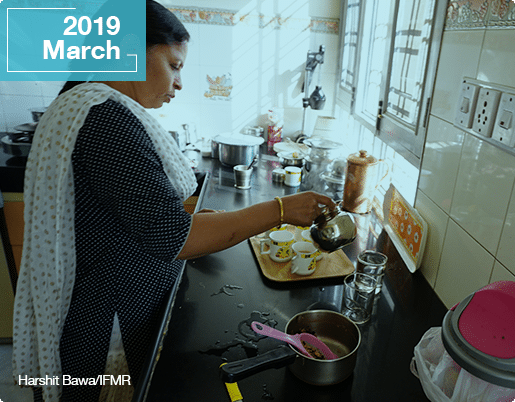

The arrangement of social structures, patriarchal system, and prevalent gender norms expect women to perform certain roles which tend to confine their choices and actions. It gives rise to complex forms of invisible gender inequalities. Gendered dimensions of housework portray the existence of such inequalities. Women are subjected to ‘dual burdens’ of household work and work performed for income-generating activities. Household work is unpaid and unrecognized and is classified as ‘unproductive work’ and no equation calculates its direct or indirect value to the economic system. Women face time deficiency for meeting their personal requirements and it is termed as ‘time poverty’ in a simpler way and is often linked to the ‘crises of care’ (Fraser, 2016). Spending long hours in unpaid housework have large implications in women’s lives which go beyond any monetary value. Women’s engagement in unpaid work constitutes to be one of the main reasons for their economic and social disempowerment. (UN Women 2018). The burden of housework and the varied demands of caring activities at the household levels restrict women’s ability to participate in work outside the home (Deshpande and Kabeer 2019). Every day, an average Indian female spends 5 hours per day in unpaid domestic work, compared to 1.5 hours by a male (NSS Time Use in India, 2019). The same report shows that 82.1 percent of women in rural India spend their time in unpaid domestic services for household members against 27.7 percent of men. Moreover, as per Jal Shakti’s Jal Jivan Mission’s Dashboard (March 2021), only 36.54% of the rural households have Functional Household Tap Connections which means that the majority of the households have to collect water from a public facility or any other water body in the village and women are more likely to be assigned with this responsibility. Less than 45% of households use clean fuel for cooking in five states as per NFHS5 (Phase1) which means that these households use traditional ways of cooking that is time-consuming and mostly women are engaged in this.

Therefore, women in rural India might face acute levels of time poverty due to multiple factors of deprivation that leave them with little time to devote to their personal well-being. Oxfam’s India Inequality Report 2020 highlighted that societal norms in rural areas do not allow women to ask men to share the burden of housework. In an article on time poverty, it is argued that “most people who are time-poor are also income-poor” and they do not have the individual choice to choose their time demands (Ghosh and Jayati 2020 p.2). It is primarily linked with their economic disadvantage which does not allow them to pay for outsourcing their housework and caring responsibilities to a third person. Moreover, in rural areas – lack of infrastructure facilities, poor availability and accessibility of goods and services, scarce public transport, and dependence on subsistence economy signify greater levels of hardship for women to complete their day-to-day activities and ultimately adding to their time poverty.

Time poverty puts stress on women’s wellbeing which goes beyond income-based poverty. Moreover, programs and interventions for women might not capture the gendered nature of time poverty when addressing women’s concerns due to the unavailability of Time Use Statistics. The inability to capture time poverty would mean that underlying factors that place women in a disadvantaged position get neglected when addressing their problems. For example, a program that aims to enhance girls learning outcomes in a government school might not take into consideration the fact that girls spend long hours engaged in housework which means they have less time available for study after school timings and ultimately impacts their learning outcomes. As per a report by UNICEF, globally girls between the ages of 5 and 14 years spend 40 percent more time, or 160 million more hours a day than boys on unpaid household chores and collecting water and firewood (UNCF 2016), Similarly, efforts to improve the political participation of women at the Panchayat level might completely neglect time deficiency as an underlying cause for lower participation of women in Gram Sabha meetings. The evidence suggests that tackling time poverty constitutes an important area of intervention to address gender inequality in rural India. For this purpose, a 4Rs Strategy is envisaged as a guiding framework to design and implement interventions in rural areas for tackling time poverty. That strategy states:

Redefine: Redefining the roles that women perform. It will require bringing a behavioral change in the men and community towards perceiving women’s roles and responsibilities and also transforming the social structures that are gender-biased.

Redesign: Redesigning the policies and frameworks that aim for gender equality. Also redesigning surveys that are well equipped to capture time poverty in women’s daily life. This will help in better availability of time use data that can extensively support the redesign and implementation of gender interventions.

Remunerate: Remunerating equally by bridging the wage gap so that women are encouraged to take part in economic activities.

Resource: Creation and access to basic infrastructure facilities and services in rural areas that can reduce women’s time in completing their day-to-day activities (collecting firewood, fetching water from a distant source, etc.). Advocating for Gender responsive care policies, puts the state at the centre of care provisioning, giving it the responsibility for framing policies that recognise and represent women and their needs in decision making arenas. There is also a potential of creating a cadre of women as a human resource through Self Help Groups who are well equipped with the knowledge, awareness and mechanism to respond to women’s demands and necessities.

Making the ‘4Rs Strategy’ a reality would require political, individual and collective actions. Governments must take efforts beyond promises for bringing the system level transformation in addressing time poverty and gender inequality. It will also require the contribution of the grass-root organizations, policy think tanks, research and gender experts on multiple fronts. At the same time it is important to involve men in the conversation, build gender perspectives bottom up and work together to create a more equal post pandemic world.

References:

Deshpande A., and Kabeer N., 2019. “(In)Visibility, Care and Cultural Barriers: The Size and Shape of Women’s Work in India,”Working Papers 10, Ashoka University, Department of Economics.

Ghosh, Jayati. “Time Poverty Is Making Indian Women Lose More Money than Ever.”ThePrint,3Oct.2020. Available from https://theprint.in/pageturner/excerpt/time-poverty-is-making-indian-women-lose-more-money-than- ever/515811/

https://ejalshakti.gov.in/jjmreport/JJMIndia.aspx

Khan R. P.,and Nikore M., 2020 “It Is Time to Address COVID-19’s Disproportionate Impact on India’s Women.” Asian Development Bank, 1 Mar. 2020.

“Nancy Fraser, Contradictions of Capital and Care, NLR 100, July–August 2016.” New Left Review, 1 Aug. 2016.

NFHS5 (Phase1), National Family Health Survey, India

NSS REPORT: TIME USE IN INDIA- 2019 (JANUARY – DECEMBER 2019). 29 Sept. 2020.

United Nations Children’s Fund, Harnessing the Power of Data for Girls: Taking stock and looking ahead to 2030, UNICEF, New York, 2016

UN Women (2018). Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment: Recognizing and Investing in the Care Economy.

- 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on women. Policy Brief. New York: United Nations

- Posted In:

- Latest Blogs

Leave a Reply