IWWAGE-Institute for What Works to Advance Gender Equality

Women in STEM in India

Women in STEM in India

Introduction

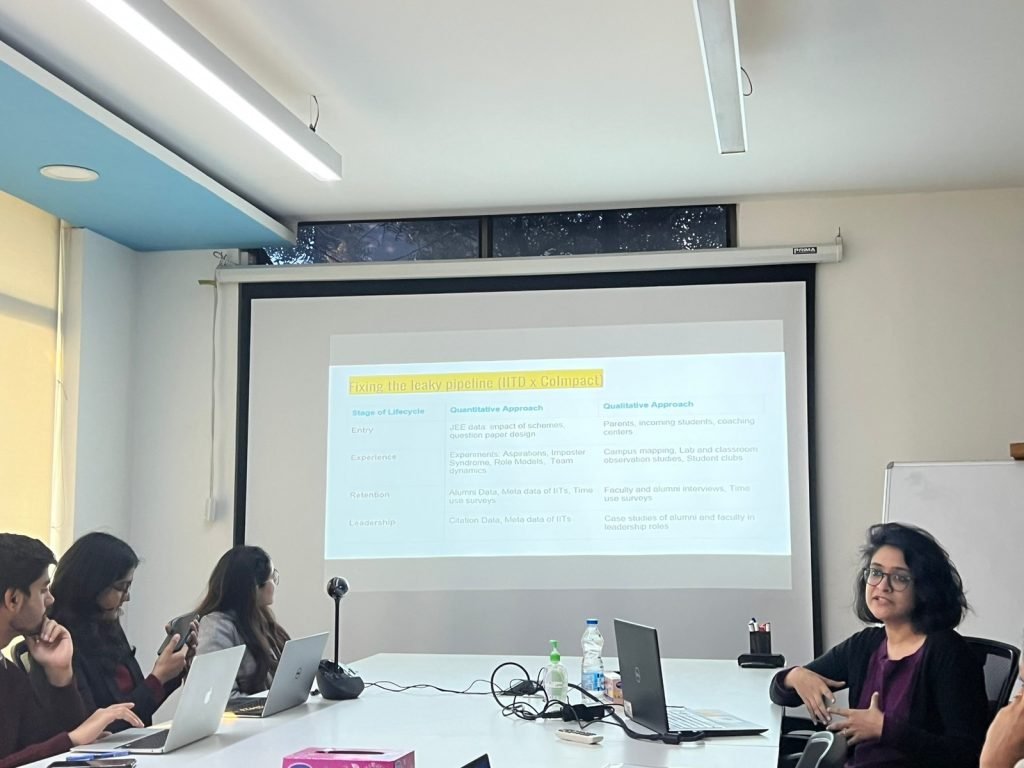

Dr Nandana Sengupta, Assistant Professor at the School of Public Policy, IIT Delhi, joined us on Jan 11, 2023to discuss the status of women in STEM in India. She talked about her personal journey, enveloping literature related to top women in STEM and discussions about the supernumerary seats scheme.

Context

- She talked about the stereotypes that she faced in school, the rampant gender divide in educational and professional settings citing an example of how women’s roles even in liberal institutions are often limited to “academic housekeeping”

- She highlighted certain statistics: India’s 135 (out of 146 countries) in Gender Parity Index (WEF, 2022); 14% base rate of STEM faculty; 43% female STEM graduates; 29% worldwide average; no female head of IIT, ISER, IISc and other decision making bodies like JEE, GATE etc.

- The literature review concerning what women had to face in STEM can be divided into four areas:

- Entry: investment in women’s education is less prominent; certain disciplines being considered masculine; parents are less favorable to send daughters to far away institutes and nature of exam

- Experience: lack of role models; absence of infrastructure like toilets; norms around socializing; women’s tendency to apply for jobs that they are 100% certain about

- Retention: nature of roles assigned to women in organizations not at par with skills and qualifications; dual burden of managing home and work;

- Leadership: Lack of networking, mentorship and leadership opportunities

- There is a reason to look at engineering field and the gender gaps in this field because

- Engineering field is the future of the job market

- The scope of engineering graduates occupying higher administrative positions, thereby encouraging women in STEM will lead to more women in administration

Deep Dive: Supernumerary Seats

- She spoke about the Supernumerary scheme i.e. Increase in female representation in IIT classrooms at least by 20% by 2020 without substantially affecting seats for male students

- Further, she threw light on the proportion of women in BTech being low as compared to other courses with ST candidates remain low overall across the courses

- The important findings from the study is that the supernumerary scheme has increased the number of females admitted to IIT with IIT Madras receiving the highest number of female students; regional variation with South India admitting more female students even in non-zonal IITs and few recommendations including reporting of data should be improved; clarification of algorithms; break the narrative of lower standards and seat stealing; support for beneficiary students, adoption of intersectional lens

Policy implications and other efforts

She further covered some policy level action that can contribute to making STEM fields accessible for women-

- DST efforts: GATI, WISE-KIRAN, INSPIRE

- Fellowships: Rukhmabai grants and short film grants on women in STEM

- Publications to educate people about the situation of women in STEM

The seminar ended with a fruitful discussion among the audience and speaker along with sharing of personal experiences.

Watch the recording of the seminar here

Intimate Partner Violence in India: Alarming Trends and Accountability measures

Ending all forms of violence against women was recognized as one of the twelve critical areas of concern by the Beijing Platform for Action. The recently concluded “Global 16 Days of Activism”, initiated by Centre for Women’s Global Leadership and carried forward by feminist groups across the world, is a collective campaign that calls to end Gender-Based Violence (GBV) by evolving the focus from awareness to accountability. Among the prevalent forms of GBV, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is one where the perpetrator not only lacks accountability but also enjoys insulation from the law as well as society.

IPV is the infliction of physical, sexual, or emotional harm committed to establish or retain a position of control/superiority by a partner in an intimate relationship. It is evident from the increasing number of gruesome cases covered by media platforms in recent times that the experience of IPV is not uncommon. This blog piece explores research and evidence on the prevalence of IPV, policies governing its redressal, and the laws instituted for its prevention and justice.

The global average prevalence of IPV among women is 30 percent according to the WHO report titled “Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates”, 2018. IPV is prevalent even in developed nations, not just in low and middle-income countries. In fact, the Nordic paradox illustrates that even countries in the region that perform well in gender equality and other development indices report a high prevalence of IPV. According to World Health Organization (2013) estimates, South Asia has the highest regional prevalence of IPV worldwide at approximately 40 percent.

India ranks 135 out of 146 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index, an instrument the World Economic Forum uses. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) has attempted to capture the incidence of IPV within India for married women since 1992. NFHS categorises IPV into three kinds: physical, emotional, and sexual violence. Physical abuse is easier to discern than the other two forms. According to the fifth and the latest round (2019-21), the incidence of a “lower” degree of violence on married women – being pushed, slapped, punched, or hair pulled etc. – is approximately 27 percent; approximately 8 percent of married women experience it in “higher” degree which includes being dragged, strangled or threatened with knife/gun, etc.; and around 6 percent married women report facing sexual abuse like physically being forced into unwanted sex acts etc.; and 13 percent face emotional abuse which includes being humiliated, tortured insulted or threatened with harm by the husband. Thus, IPV can take a wide range of forms perpetuated by several factors including socio-cultural and economic aspects.

NFHS data finds that the incidence of IPV is lower for women with better access to resources required for well-being and growth, like access to education, household wealth, and information. For instance, with increase in the level of education, the incidence of all the three forms of IPV decreases. The largest decline is seen in physical abuse of less severe form across most of the aforementioned factors. For example, the incidence of abuse for women with no education is 36 percent and it falls to 13 percent for those who obtained higher levels of education. Similarly, living in urban areas reduces the chances of abuse by 7 percentage points as compared to those residing in rural areas. Also, belonging to the richest quintile as compared to the poorest, leads to a fall in the incidence of abuse by 20 percentage points. However, these are assumed to be gross underestimates of reality because of the under-representation of the richest quintile in household surveys.

Apart from the socio-economic background, intergenerational violence impacts the level of incidence of violence. Intergenerational transmission of violence means that children of violent offenders are more likely to commit violence. If men are exposed to household violence, the incidence of violence increases by 11 percentage points. Women are more likely to face and accept violence if they have witnessed the same; in this case, the incidence of IPV increases by 33 percentage points.

Also, NFHS collects information to gauge the normative behaviour of married couples. It asks questions targeted to both husband and wife to understand whether beating the wife is justified in different scenarios such as: if she goes out without telling her husband, if she neglects children, if she argues with her husband, if she refuses to have sex, and if she burns food. Women face 21 percent more abuse by their husbands if they accept being beaten and the incidence of violence by men increases by 8 percent if they justify beating their wives.

While these forms of violence may be categorised differently for the sake of data collection, they can be committed all at once. For example, denial of physical intimacy by women in romantic relationships might lead to emotional manipulation or disregard for consent by men. If women resist, physical and sexual violence might follow as a response to the woman’s defiance. This way men escalate the violation of women’s autonomy and establish control. Contrary to popular belief, frequent expression of care, concern, and love doesn’t necessarily mean an absence of violent behaviour. All these acts coexist and are indicative of larger societal issues and deep-rooted hegemonic masculinity that creep into intimate spaces which go unreported.

The normalisation of these crimes and victim-blaming by society makes it harder for women to speak up and report it officially. In this context, there is a slew of schemes for the upliftment and empowerment of women, but little effort is directed towards working with the perpetrators of violence i.e. there isn’t enough engagement with men and boys, and the issues caused by convoluted ideas of masculinity prescribed by patriarchal norms. The cultural acceptance of IPV that stems from the belief that men are entitled to women’s bodies in intimate relationships effectively results in condonement of male violence. There is an urgent need to focus on assigning accountability to the perpetrator and strengthening the legal system to provide sufficient recourse and a conducive ecosystem where women can report cases of IPV without facing negative consequences.

IPV is a complex issue because of the nature of the relationship the woman shares with the perpetrator. Ad-hoc solutions to such problems do not help in reducing these acts of violence. Instead, there is a need for policies, practices, and awareness generation around IPV. One of the biggest challenges is working towards the social acceptance of victims of IPV and holding the perpetrator accountable at the same time. There have been instances where even law enforcement agencies like the police play a reconciliation role. Therefore, bringing about shifts in social consciousness is critical.

There is a need to take concrete steps like gender sensitisation at different levels – families, communities, educational and state institutions for awareness generation, developing infrastructure like mental health centres using trauma-informed approaches that are pertinent for supporting women in need, and introducing methods of counselling targeting the perpetrators in order to end the cycle of violence. The frequent call for empowering women cannot exist in isolation and needs to be backed with substantive measures being taken to overhaul policies, legislations, criminal codes, reformed police systems, and infrastructure required to address IPV.

Note: Unless otherwise mentioned, the data in this blog piece is drawn from NFHS 5.

Aparna G, a Research Associate with IWWAGE, is engaged in studying female labour force participation. Her research interests include applied microeconomics and intersectional political economy.