Background: Gender Samvaad is a national virtual platform of DAY-NRLM used to generate greater awareness on DAY-NRLM’s interventions across the country. It is also an opportunity to share and learn best practices amongst the States Rural Livelihoods Missions and hear voices from SRLM cadres and SHG women. Two such events have been held earlier on 16 April 2021 and 2nd July 2021. The third Gender Samvaad event was organized to highlight issues around food & nutrition security and initiatives undertaken by the State Rural Livelihoods Missions and SHG members for the same. The United Nations standing committee on nutrition defines food and nutrition security as:

“Food and nutrition security exists when all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to food, which is consumed in sufficient quantity and quality to meet their dietary needs and food preferences, and is supported by an environment of adequate sanitation, health services and care, allowing for a healthy and active life.” Food Security has 4 dimensions: Availability, Access, Utilization and Stability of food while Nutrition Security includes the additional dimensions of Care and feeding practices and Health and Sanitation.

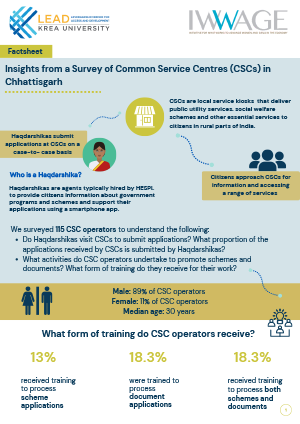

Integrating FNHW within DAY-NRLM: In 2019, the DAY-NRLM adopted a ‘Dashasutra’ strategy for SRLMs, under which Food Security, Nutrition, Health and WASH (FNHW) and Gender are included as essential components needed to bring about social development. This inclusion of FNHW demonstrates the commitment of DAY-NRLM to contribute to overall improvement in health and nutrition of the community. Provision of food and nutrition security is an essential part of the FNHW strategy. To ensure the four dimensions of food security, i.e. Availability, Access, Utilization and Stability of food, DAY-NRLM envisages the following approaches, (1) establishment of nutrition garden and home consumption of produce of nutrition gardens by SHG families (2) increase in access of SHG households to Take Home Rations (THR) under ICDS (3) Promotion of nutrition-sensitive agriculture, (4) Improved coverage of SHG households under Public Distribution System (PDS) and (5) Addressing gender issues related to consumption of food. The effective operationalization of these approaches can be achieved through inter-departmental convergence between DAY-NRLM and M/oWCD, Ministry of Agriculture and Food and Public Distribution and intra-departmental convergence between FNHW and Farm Livelihoods verticals.

FNHW through a gender lens: In India, an effort for health and nutrition cannot reach fruition if certain critical issues are not addressed. Evidence demonstrates that, equitable distribution of food within the family is not achieved without addressing the GENDER NORMS. The common practice of women eating last, least and leftovers inhibits women from reaching their optimum nutritional potential, even if there is availability of adequate food in the home. Decisions on procurement of food products and their distribution within the family are also often taken by the head of the household who are mostly men, keeping members like women, young children and elderly at the fringes within the home. With this in mind, DAY-NRLM incorporates a gender lens while designing interventions around all aspects of social development. This gender intentional approach is being used in efforts for food and nutrition security as well.

Institutional partnerships to strengthen FNHW interventions for better gender outcomes

i) Promoting convergence between Farm Livelihood and FNHW of DAY-NRLM, MoRD for establishment and utilization of nutrition gardens by SHG families: The Ministry of Rural Development has been undertaking several steps to enhance promotion of nutrition gardens at household, community, Anganwadi and panchayat land across the country through DAY-NRLM and MGNREGA. A detailed Advisory was shared with SRLMs by the Farm Livelihoods (FL) vertical of DAY-NRLM to establish nutrition gardens, in May 2019. This was further supplemented by including work done for developing nutrition garden under the ambit of MGNREGA through a DO letter in August 2020. Additional thrust was given to this effort during the Poshan Maah, 2020, when the MoPR, MoRD and MoWCD issued a Joint Directive to all State Chief Secretaries to conduct a month-long drive to plant nutrition garden to enhance Food Security. As a result of these concerted efforts, 77.89 lakh Agri-Nutrition Gardens have been promoted across the SRLMs till December, 2021.

Evidence suggests that the mere presence of a nutrition garden at home does not translate into equitable gender norms for improved dietary diversity. There is a gap between having access to food and actually consuming it. Hence, along-side growing food, families also need to be counseled to include the produce of nutrition garden in their daily diet. Under FNHW component of DAY-NRLM, awareness sessions on diet diversity have been initiated through monthly discussion in SHG meetings and counseling the families through community-based events, home visits, village events etc. Some SRLMs have progressed in this regard, and Gender Samvaad could be an appropriate forum to share their experience with other SRLMs. Also the message of combining nutrition garden establishment with Social Behaviour Change Communication (SBCC) to emphasize the importance of planting nutrition gardens and supplementing it with counseling for behavior change so that each family consumes the produce of the garden, thereby improving diversity in their diet and moving a step further towards reaching a state of Nutritional security can be reiterated. Such dialogue will also enhance the opportunity of convergence within DAY-NRLM verticals and concerned departments.

ii) Promoting convergence between MoRD and MoWCD to improve access of SHG women to Take Home Rations (THR) and other services: The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD) launched the ICDS program on 2nd Oct 1975 and it remains one of the critical pillars for provision of food in the form of Take Home Rations (THR) and fresh cooked meals for pregnant and lactating women, children below 6 years of age and adolescent girls (under the SAG scheme). Under DAY-NRLM, SHG family with pregnant and lactating women, children below 6 years and adolescent girls are encouraged to avail the THR services from the local Anganwadi Center. A few SRLMs have collaborated with DoWCD for engaging SHGs producing and providing THR to Anganwadi Center.

iii) Promoting convergence between M/oRD and Ministry of Agriculture: Agricultural practices/cropping patterns also play a significant role in the access to foods for a community, which impacts their dietary pattern. Despite producing large quantities of nutrient-rich crops such as Rice, Pulses, Millets etc, India harbours one-third of the world’s stunted children. Evidence suggests that a move towards cultivation of nutrient-rich indigenous food crops such as Jowar, Bajra and other millets and diversification of crops can benefit the nutrition status of the local community. Women empowerment through Agricultural initiatives also has an important role to play in improving overall nutritional status.

iv) Convergence between MoRD and Department of Food and Civil Supplies for improved coverage of SHG households under Public Distribution System (PDS): Similarly, the Public Distribution System (PDS) plays a crucial role in reducing food insecurity by acting as a safety net by distributing essentials at a subsidized rate. With a network of more than 400,000 Fair Price Shops (FPS), the Public Distribution System (PDS) in India is perhaps the largest distribution machinery of its type in the world reaching 80 crore persons in the FY 2020-21. Under DAY-NRLM, linking of SHG members with entitlements and services are encouraged including access to subsidized food and other household materials under the PDS.

Objectives of 3rd Gender Samvaad:

- To inform participants about the benefits of nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition garden in supplementing availability of diverse food groups at household level;

- To reinforce the significance of gender sensitive approaches while conveying nutrition messages to promote equity among men and women in consumption of food at home;

- Experience sharing between SRLMs on various learning and challenges faced during the implementation.

AGENDA

| Time |

Session |

Speaker |

| 3:30 – 3:40 pm |

Welcome and Opening Remarks |

Smt. Nita Kejrewal

Joint Secretary, MoRD |

| 3:40 – 3:45 pm |

Video on role of SHG members in addressing malnutrition |

Smt. Nita Kejrewal

Joint Secretary, MoRD |

| 3:45 – 4:00 pm |

Initiatives under DAY-NRLM and need for convergence by MoRD |

Sh. Nagendra Nath Sinha

Secretary, MoRD |

| 4:00 – 4:05 pm |

Video on POSHAN Maah-2021 activities under DAY-NRLM |

Smt. Nita Kejrewal

Joint Secretary, MoRD |

| 4:05 – 4:25 pm |

Keynote Address |

Dr. Vinod Kumar Paul

Member, NITI Aayog |

| 4:25 – 4:40 pm |

Addressing nutritional requirements of Women & Children through ICDS/POSHAN Abhiyaan & role of Self-Help Groups

by MoWCD |

Shri Dhrijesh Tiwari

Statistical Adviser, MoWCD |

| 4:40 – 4:55 pm |

Women’s rights & entitlements for food & nutrition security & role of government institutions by National Commission for Women |

Ms. Meeta Rajivlochan Member Secretary, NCW |

| 4:55 – 5:10 pm |

Presentation on behavioural change communication around FNHW activities and nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices undertaken in the State by SRLM, Bihar |

Shri Balamurugan D, Secretary, Rural Development Deptt., Government of Bihar cum CEO, BRLPS, SRLM

CRP – 5 mins

CEO – 10 mins |

| 5:10 – 5.25 pm |

Presentation on Nutrition Enterprises and other aspects of Nutritional Security by SRLM, Maharashtra |

Dr. Hemant Wasekar, CEO, SRLM, Maharashtra

CRP – 5 mins

CEO – 10 mins |

| 5:25 – 5:40 pm |

Evidence for role of Women’s Collectives in facilitating Household Food Security by IFPRI |

Ms. Kalyani Raghunathan, IFPRI |

| 5:40 – 5:55 pm |

Presentation on successes, challenges and way forward for Maitri Baithak and Pariwar Chawpal by SRLM, Chhattisgarh |

Smt. Effat Ara, Incharge-Mission Director, SRLM

Chhattisgarh

CRP – 5 mins

CEO – 10 mins |

| 5:55 – 6:10 pm |

Question & Answer |

Moderator |

| 6:10 – 6:15 pm |

Closing remarks and vote of thanks by MoRD |

Sh. H.R Meena

Deputy Secretary, M/oRD |